EMMA BATHA and BAHAAR JOYA, of Thomson Reuters Foundation, report that people smugglers are more than doubling fees for some routes as they cash in on an exodus fleeing the Taliban…

London, UK

Thomson Reuters Foundation

As a female prosecutor in Afghanistan, Shafiqa Sae knew she had to flee for her life when the Taliban seized power – what she did not realise was just how much it would cost.

Smugglers are exploiting Afghans’ desperation to leave the country, hiking prices after demand grew for their services and borders became harder to cross.

Afghans who have fled to Pakistan since the Taliban takeover on 15th August last year said members of the Pakistani security forces had also milked them for bribes and some landlords had doubled or trebled rents.

“Everyone is taking advantage of our plight to make money off us,” Sae told the Thomson Reuters Foundation from Pakistan’s capital, Islamabad.

Shafiqa Sae and her family are pictured in a van after crossing the border into Pakistan. PICTURE: Thomson Reuters Foundation

The Taliban’s lightning capture of the country has prompted a mass exodus of Afghans fleeing persecution and poverty.

But border closures by Pakistan, Iran and other neighbouring countries, combined with the difficulty of obtaining a passport or visa, have pushed many to turn to smugglers.

“Everyone is taking advantage of our plight to make money off us.”

– Shafiqa Sae.

Those making the risky journeys often take gruelling desert and mountain treks. Some tunnel under border fences. Others use fake IDs.

The Mixed Migration Centre, which monitors smuggler prices, said fees had already jumped during the COVID-19 pandemic as travel curbs made it harder to move around, but the scramble to get out of Afghanistan since August had sent prices soaring.

Sae, 26, fled the capital, Kabul, with her mother and seven siblings on 25th August after a foreign benefactor paid a smuggler $US5,000 to get them out.

The prosecutor’s family are Hazaras, a predominantly Shi’ite minority who were targeted by the Taliban when they last ruled from 1996-2001.

The Islamist group’s return to power left Sae in fear of her life. Not only had she helped put Taliban members behind bars, but she had been active in protests against the group and was a vocal advocate for women’s rights.

Before leaving Kabul, Sae’s mother was fitted with a fake cannula and intravenous drip.

Pakistan still allows Afghans to cross for emergency medical treatment without visas, and the family hoped the border guards would take pity.

Shafiqa Sae is pictured in Islamabad. PICTURE: Thomson Reuters Foundation

The trick worked, helped by a few dollars slipped to the right people.

Once across the border, the demands for bribes mounted. Fourteen checkpoints later and they were $US300 poorer.

In Islamabad, Sae said their landlord was charging them three times the local rate. They had also handed him $US700 to pay off the police as it is illegal to rent to Afghans without visas.

People smugglers now charge Afghans an average of $US140-$US193 to reach Pakistan via the border town of Spin Boldak, up from $US90 a year earlier, according to data from the Geneva-based Mixed Migration Centre.

Average fees for Iran via the smuggling hub of Zaranj are $US360-$US400, compared to about $US250 previously, it said.

Charges vary depending on the length and difficulty of the route, the wealth and ethnic background of the person making the journey, whether they have contacts, and the number of people demanding bribes.

Several Afghans interviewed by the Thomson Reuters Foundation cited much higher fees than those reflected in data collected by the Mixed Migration Centre.

One woman said she was recently quoted $US1,000 for the trip to Islamabad with her two children.

Abdullah Mohammadi, an expert at the Mixed Migration Centre, said smugglers were usually part of well-established organised criminal networks.

However, with Afghanistan hammered by an economic crisis and severe drought, farmers desperate for money to feed their families have also become involved.

“They know what they’re doing is wrong, but say they don’t have any other options,” Mohammadi said.

“The criminal networks are benefiting because they can use these people to expand their operations.”

The Taliban also benefit. The BBC reported that smugglers openly ferrying Afghans from Zaranj to Iran paid local Taliban about $US10 per pickup truck.

The Norwegian Refugee Council reported in November that up to 5,000 Afghan refugees were fleeing to Iran every day, although many are deported.

Most go via Pakistan, but Mohammadi said smugglers were increasingly using a shorter, more precarious route which requires climbing over or tunneling under barriers erected on the Iranian border.

Although there is a higher chance of getting caught, the route is often favoured by Hazaras who risk attacks by militant groups on the traditional routes through Pakistan because of their ethnicity.

Smugglers can charge Hazaras about a third more than non-Hazaras because of the increased risks from the Taliban, Jundallah and other militia, Mohammadi said.

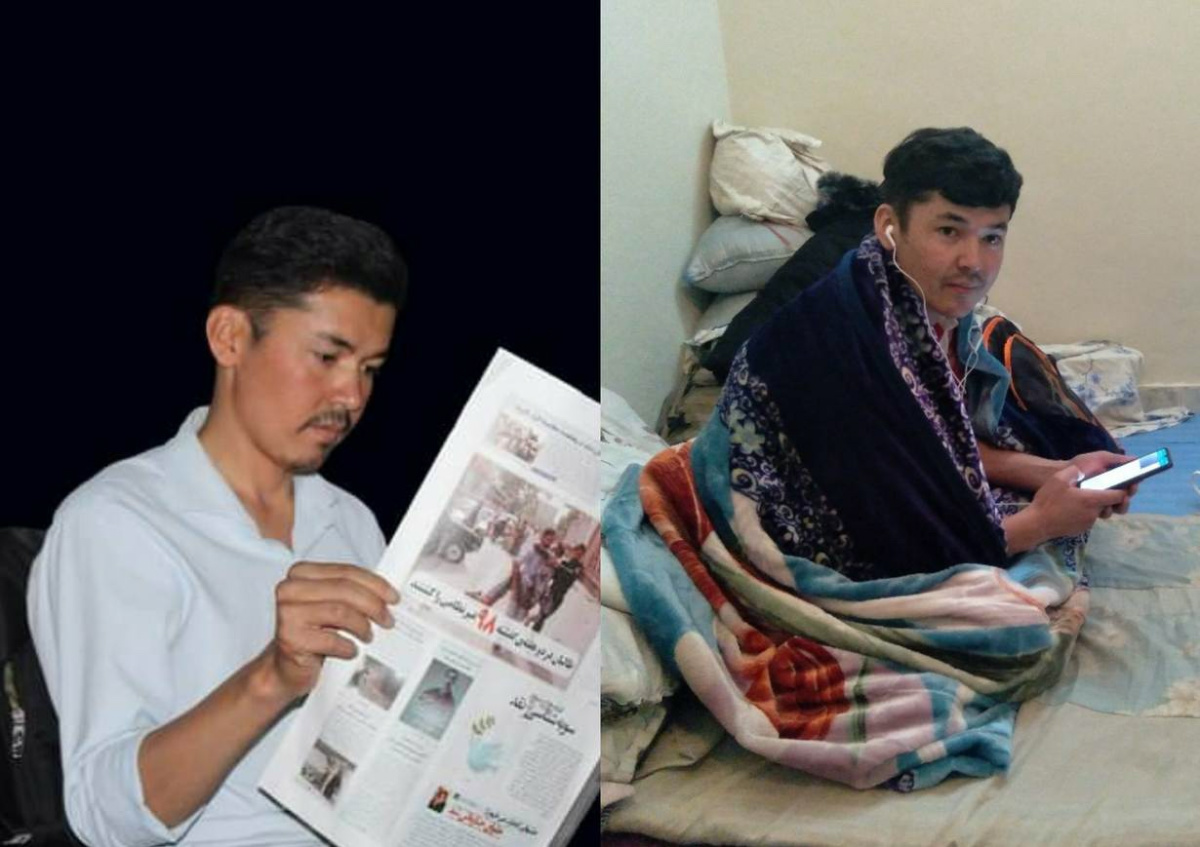

Left: Afghan journalist Ismail Lali is seen in Kabul in this undated photo; Right: Lali sits in his room in Quetta, Pakistan, after leaving Afghanistan in August. PICTURE: Thomson Reuters Foundation

Journalist Ismail Lali, 28, said smugglers were making a fortune out of the crisis.

“People are so desperate to leave that they can just charge them whatever they like,” said Lali, who is also a Hazara.

He paid a smuggler $US700 in August to take him to the Pakistani city of Quetta, including bribes, but friends report the fee is now $US800.

“It’s become a lucrative business for smugglers, and also for the Pakistani police,” he added.

Since arriving in Quetta, he said he had paid police $US200 in bribes after being repeatedly stopped and threatened with deportation. He dares not go out now.

A senior police inspector in Quetta said officers were under strict instruction not to harass Afghans.

Security forces who staff checkpoints did not immediately respond to calls.

We rely on our readers to fund Sight's work - become a financial supporter today!

For more information, head to our Subscriber's page.

Migration experts expect some Afghans in Pakistan and Iran to move towards Turkey and Europe in the spring.

In January, the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, launched a $US623 million appeal to support Afghans in neighbouring countries and their host communities.

It has also urged countries to keep their borders open and halt deportations.

The UNHCR said Iran had returned more than 1,100 Afghans a day in January. Smaller numbers have been deported from Pakistan.

They include Sae’s mother and three sisters, who were sent back in December.

The Taliban have already visited the family in Kabul to ask after the prosecutor’s whereabouts.

Sae rarely leaves her Islamabad apartment, terrified of deportation.

“Either the Taliban will kill me, or the prisoners they have released will kill me,” she said.