MARÍA TERESA HERNÁNDEZ, of Associated Press, reports on the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo…

Buenos Aires, Argentina

AP

Forty-seven years ago, before her hair turned white and she had no need of a wheelchair to march around Argentina’s most iconic square, Nora Cortiñas made a promise to her son who disappeared: She would search for him until her last breath.

Her commitment sums up the driving force of Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, a human rights organisation created by women whose children were kidnapped by the military dictatorship that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983.

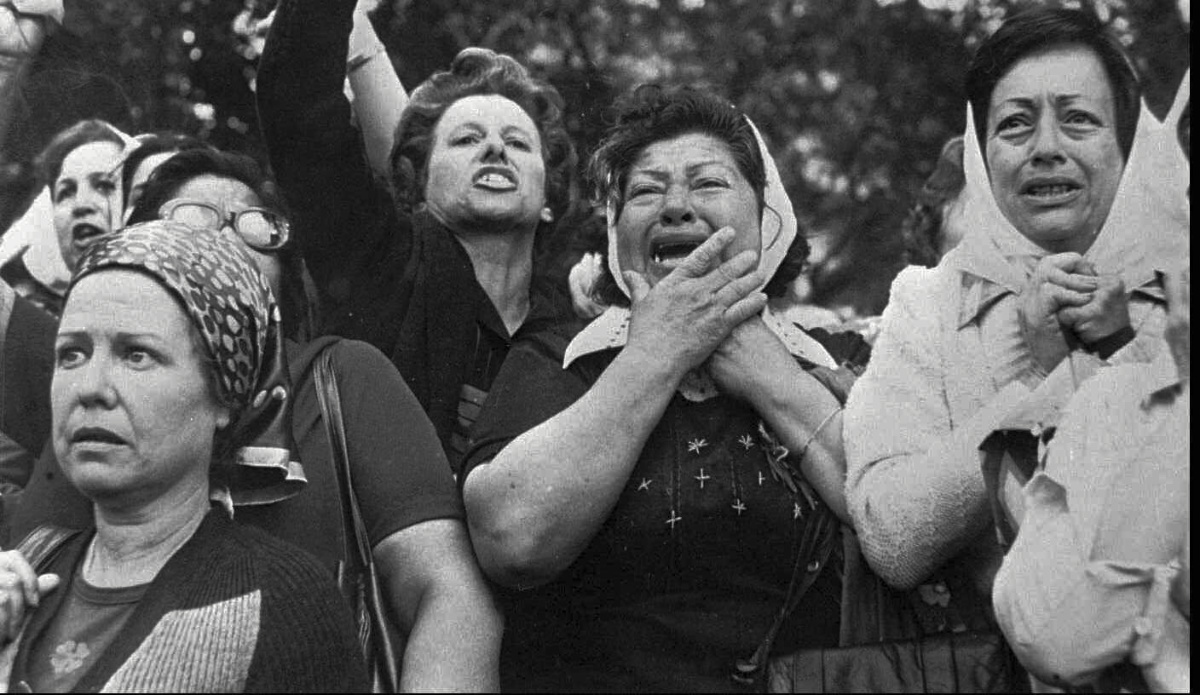

The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and their supporters march in memory of Hebe de Bonafini, leader of the group of women whose children were kidnapped by the military dictatorship (1976 – 1983), and whose own two sons were arrested and disappeared, in the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 20th November, 2022. Week after week, since April 1977, the mothers of disappeared children have gathered at the square that provided the group with its name, despite being discredited during the dictatorship as “crazy” and “terrorists.” PICTURE: AP Photo/Gustavo Garello/File photo.

With time, their fight became a symbol of hope and resistance. Their wounds are shared by thousands who protest every year, on 24th March, to remember the beginning of the bloodiest period of their country’s history.

“They represent the fearless fight of a lot of women who, at all costs, sought the tools to deliver a message,” said Carlos Álvarez, 26, during a recent protest against Argentine President Javier Milei. “None of my relatives disappeared, and I still empathise with their struggle.”

“They represent the fearless fight of a lot of women who, at all costs, sought the tools to deliver a message. None of my relatives disappeared, and I still empathise with their struggle

– Carlos Álvarez

Milei, a right-wing populist who took power in 2023, has minimised the severity of the repression during the dictatorship, alleging that human rights organisations’ claim of 30,000 disappearances during that period is false.

Long before Milei, when the military ruled, mothers like Cortiñas were discredited as “crazy” and “terrorists”, but their quest to learn what happened to their children never ceased.

Week after week, since April 1977, Mothers of Plaza de Mayo have gathered at the square that provided the group with its name. Together with Argentines who hurt with injustices of their own, they meet each Thursday, at 3:30pm, and circle around Plaza de Mayo’s pyramid.

“The story of my life is the story of all Mothers of Plaza de Mayo,” said Cortiñas, who will soon turn 94. “We don’t know anything about our children. A disappearance means you don’t know anything; there is no way to explain it.”

Her eldest son, Gustavo, was 24 when he disappeared on his way to work. An admirer of Evita Perón, he was a militant of Montoneros, a Peronist guerrilla organisation whose members were targeted by the military in the 1970s.

“When they took my son, on April 15, 1977, I went out to look for him and I encountered other mothers whose children had also been kidnapped,” Cortiñas said.

Members of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo protest in San Martin Square in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 21st November, 1977. PICTURE: AP Photo, File photo.

Filled with uncertainty, Cortiñas and other mothers held their first gatherings at a local church where the bishop offered nothing but disdain. Frustrated, one of them said: “Enough, we need to gain visibility.”

They headed to Plaza de Mayo, where the presidential office is located, and where police unexpectedly provoked their symbolic march around the square.

A state of emergency was in place, preventing Argentines from gathering, so police officers screamed at them: “Move, ladies, move!”

And so, in pairs, crying silently without knowing that they would come back every Thursday for the rest of their lives, the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo walked.

By October 1977, when Mothers of Plaza de Mayo decided to join a pilgrimage to the city of Luján, most of them felt let down by the Catholic Church.

Though they sought the church’s help and comfort, many of their once trusted priests told them to go home and pray.

To gain exposure, one mother suggested carrying a pole with a blue or red cloth, but another replied that it wouldn’t be visible. “Let’s use one of our children’s diapers to cover our heads,” another mother said. “We all keep at least one of them, right?” And they all did.

After the pilgrimage, while other parishioners prayed for the Pope, the sick and the very same priests who turned their back on them, the mothers prayed for the disappeared.

Cortiñas treasures the scarf she wore that day. She has had four or five scarves since then, with her son’s name embroidered in blue thread.

“It makes me very proud, knowing they bear Gustavo’s name,” Cortiñas said. “He was a fighter, one of those who are necessary nowadays to change the world.”

Nora Cortinas, 94, poses for a portrait wearing a photo of her disappeared son Gustavo at her home, decorated with a mural of her, on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, Argentina, on Monday, 29th January, 2024. Cortinas became one of many mothers whose children were kidnapped by the state when Gustavo disappeared on April 15, 1977, giving birth to what is today’s human rights organisation, the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo. PICTURE: AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko.

Cortiñas never leaves her home without her white scarf. She mostly wears it during the Thursday march at Plaza de Mayo, but she always keeps it inside her handbag, next to a picture of Gustavo that she hangs from her neck at public events.

The scarves have multiplied over four decades. They can be seen on murals, tiles, pins and protest signs.

“I see them, and I feel hope,” said Luz Solvez, 36, on a recent day in Buenos Aires. “It is a symbol that summarises part of our history. All the cruelty, how horrible it was, but also how they [the Mothers] took it on the side of justice instead of revenge.”

A few years ago, Graciela Franco’s daughter asked her to get identical tattoos. Franco wanted it “to be something truly meaningful.” Now, mother and daughter have a row of scarves on their forearms.

We rely on our readers to fund Sight's work - become a financial supporter today!

For more information, head to our Subscriber's page.

Since 2017, Franco has worked with ceramist Carolina Umansky on a project called “30 Thousand Scarves for Memory“, which honours the 30,000 people who disappeared during the dictatorship.

They have produced and given away 400 ceramic tiles with images of scarves to symbolize the Mothers’ fight and the need for historic memory. Their hope is that the tiles be placed in plain sight, particularly at entrances to homes.

“The idea is that they permanently generate a question,” Umansky said. “That anyone who looks at them asks: Why is this scarf in this house?”

A mural of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, whose children disappeared during the military dictatorship (1976 – 1983), covers a wall at the Museum of Space for Memory and the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (ESMA) in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on Tuesday, 19th March, 2024. The ESMA was once the Navy School of Mechanics and housed the most infamous illegal detention centre during the dictatorship. PICTURE: AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko.

Taty Almeida’s feels as if her old self — the one before her son Alejandro, 20, went missing – is gone. His disappearance so profoundly changed her that it’s as if she’s been reborn in her despair and search for him.

“Alejandro gave birth to me,” Almeida, 93, said. “I am happy to have given birth to my three children, but Ale gave birth to me.”

She was unaware of her son’s militant connections when he vanished in June, 1975. She was a deeply Catholic woman, raised by an Argentine general, who wrongfully blamed the Peronists for his disappearance.

“I couldn’t think that my acquaintances [the military] were the culprits,” Almeida said. “I went to them, but never got any help.”

For four years, she looked for her son on her own. It wasn’t until 1979 that she found the courage to approach the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo.

We rely on our readers to fund Sight's work - become a financial supporter today!

For more information, head to our Subscriber's page.

With her background, she worried they would think she was a spy. But once inside the house that they used as a headquarters, no one asked her political affiliation, religion or personal views. Just the one question all aching mothers were asked: “Who are you missing?”

“When they touched the most precious thing a woman has, a child, we went out like crazy, as they called us, to scream, to raise questions, to look for our children,” Almeida said.

Her faith is not lost but changed. Though she no longer attends Mass and is aware of the complicity that the Catholic Church played during the dictatorship, she still believes in God.

Taty Almeida waves during an event marking International Women’s Day in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 8th March, 2024. Almeida’s 20-year-old son Alejandro vanished in June 1975. For four years she searched on her own for her son but in 1979 approached the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, worried that with her family’s military background, they would think she was a spy. PICTURE: AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko,/File photo.

After 48 years of searching, she wears her white scarf to all protests and shares her story with journalists and younger generations, who she trusts will take the lead once the Mothers are all gone.

“I’m sure that Alejandro is very proud of me,” Almeida said. “That gives me strength.”

She wonders what he would look like today. Perhaps now, at age 69, would his curly hair have turned gray? Would he wear glasses? Would he have given her grandchildren?

“I always say that Alejandro is present, but no. He is gone.”

Even so, she says, there will always be hope and the fight does not end.

Argentine forensic anthropologists are identifying more and more remains of people who disappeared during the dictatorship. If they were to find Alejandro’s remains, she could finally grieve, bring him flowers, pray to him.

“I don’t want to leave without first, at least, being able to touch Alejandro’s bones.”