DAN WOODING, founder of Assist News Service, tells of how spending time in Uganda in the aftermath of the terrible rule of Idi Amin changed his life…

Actor Forest Whitaker took a step closer to being named the next Oscar best actor, after beating Leonardo DiCaprio, Will Smith and Peter O’Toole, for his role as Idi Amin in The Last King Of Scotland at the recent Screen Actors Guild Awards in Beverly Hills, California.

On hearing this news, memories came flooding back to me of how Idi Amin took my life in a completely different direction at a time when my future was looking bleak.

RECALLING A DARK TIME: Forest Whitaker stars as the former Ugandan dictator Idi Amin in ‘The Last King of Scotland’.

“Strangely enough, it was Idi Amin, a former heavyweight boxer, who stood at more than 1.9 metres tall and weighed 122 kilograms, who changed my life and helped me find a new mission – helping the persecuted church.”

Amin died at the age of 78 on August 16th, 2003, in King Faisal Specialist Hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where he had been in a coma and on life support since his admission on July 18th of that same year. The crazed Ugandan dictator had ruled by terror for eight terrible years in from 1971 to 1979, and whose regime was reported to have been responsible for the deaths of 500,000 of his countryman.

But strangely enough, it was Idi Amin, a former heavyweight boxer, who stood at more than 1.9 metres tall and weighed 122 kilograms, who changed my life and helped me find a new mission – helping the persecuted church.

It was in May, 1979, that Idi Amin had been routed by the Tanzanian Army and had fled to Libya to be sheltered by his friend, Muammar Gaddafi, then later was taken in by Saudi Arabia, that an old friend, Ray Barnett, came back into my life. Ray, an Irish-Canadian who had founded Friends in the West and later began the African Children’s Choir, had previously taken me on a reporting trip to Russia and often looked me up when he was in London, turned up at the Stab-in-the-Back pub in New Fetter Lane, London, England, where I was, as usual, drinking too much.

Ray, who was born in Colerain, Northern Ireland, and later settled in British Columbia, Canada, was aware that I was desperately unhappy in my life as a tabloid reporter with the Sunday People newspaper and really wanted to get my life back on track with God.

In the smoky bar filled with cynical London hacks, Ray shared with me the incredible story of the courageous Christians of Uganda who had survived the “Uganda Holocaust.” He explained that 300,000 believers were among those who were slaughtered during the mass killings of those eight years of Amin’s misrule.

He then challenged me to give my life and talents back to the Lord; quit my job and travel with him to Uganda to write a book on what had happened in that country. His timing couldn’t have been better and that night I recommitted my life to the Lord, agreed to quit my job on one of Britain’s largest circulation newspapers, and fly to Uganda with him to begin work on the book which was eventually published by a British publisher and also by Zondervan in the United States. It was called Uganda Holocaust.

We flew from London to Nairobi in Kenya and then onto Entebbe Airport and as we were touching down, Ray turned to me and said, “Well, Dan, you’ve gone and done it.”

I smiled wryly. “Yes, I have. You know, on the last day at the paper they had a reception and all the staff sang All Things Bright and Beautiful’ for me. I think they must have made history. I don’t think a hymn’s ever been sung in the Sunday People newsroom before.

“I’m glad I’m out, but it was quite a wrench. It was as if I had a ladder up to a building which was my career. I had crawled and scratched my way to the top and when I got there I discovered I had the ladder against the wrong building all the time…”

As the plane touched down on the runway at the battle-scarred airport, the passengers, mainly Ugandan refugees returning home, clapped joyously as the hostess said “Welcome home!”

In Nairobi, we had approached World Vision International and they agreed to allow Ray and me to join one of their relief reconnoiters, and to travel with them in a Volkswagen Kombi that would take us on the long, hair-raising journey into the very heart of the Uganda holocaust. Joining Ray and me on that trip was Dan Brewster, an American who was relief and development associate at the World Vision office in Africa.

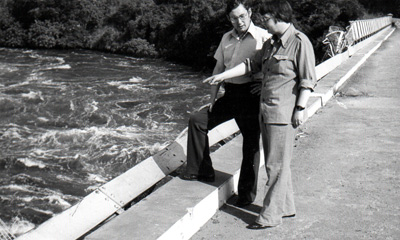

A DIFFERENT WORLD: Ray Barnett (left) and Dan Wooding at Entebbe Airport in 1979.

Now at Entebbe, we clambered down the steps of the plane to be greeted by a hot, stuffy billow of air, and I noticed a huge presence of Tanzanian troops. About three hundred yards from our plane, the notorious “Whisky Run” jet stood motionless and riddled with bullets. This Boeing 707, bearing the black, red, and yellow insignia of Uganda Airlines, used to make a weekly 14-hour flight to Stanstead Airport in England, where Amin’s men would load it up with booze (even though they were Muslims) and other “goodies” for the killer squads. The Ugandans paid for this with cash from the sale of coffee. Often there were as much as 40 tons of goods in the airplane’s hold. Whisky was always a priority. It was Amin’s way of buying their loyalty.

As we walked into the devastated terminal, it was amusing to see a table with a single immigration official, parked in the middle of the twisted mess. I presented my passport and before he even looked at it, he fixed me with a baleful stare and asked in an eerie, controlled voice, “Do you have any Kenyan newspapers? It gets so boring here with only two flights a day.” (One was from Kenya, the other Zaire.)

I lamely handed him a Nairobi newspaper, so he stamped my passport. Obviously documentation didn’t mean too much, as long as I had something for him to read.

When the three of us got through customs, we were met by Geoffrey Latim, a former Olympic athlete who had fled the country during Amin’s reign. He was to be our guide. Latim led us to a Christian customs officer who, while being watched by a poker-faced Tanzanian soldier armed with a rifle, made a token check of our bags.

“There is no phone link with Kampala and little or no petrol (gasoline),” explained Latim. “So we might be in for a long wait until a driver arrives for us. He dropped me off and said he would be back later.”

Latim was right. During that time, the Christian customs official, who turned out to be from the Acholi tribe, joined us for a chat. He shared with us how God had saved his life. “I was going to be killed on April 7th, 1979,” he said. “But on the 6th, Entebbe was freed by the Tanzanians and my life was spared.”

The man revealed that his name was on a death list found when the State Research Bureau headquarters at Nakasero, Kampala, was liberated by the Tanzanians. He looked sad as he told of the heartbreak of his job during Amin’s rule. “I saw many people passing through customs and I knew there was no way they would reach the aircraft,” he said tragically. “They would be intercepted by the State Research men and never be heard of again. These terrible killers were all over the airport. Most of them were illiterate and had gotten their jobs because they were of the same tribe as Amin.”

Eventually the Kombi arrived and we began the 30 mile journey to the capital. We were stopped at several road blocks set up by the Tanzanians, and Latim patiently explained to the positively wild-looking soldiers – most of whom were carrying a rifle in one hand, a huge looted “ghetto-blaster” playing loud, thumping disco music in the other – why we were in Uganda. Burned-out military hardware, including tanks, littered the sides of the main highway to Kampala.

Soon we were at the Namirembe Guest House, run by the Church of Uganda, but originally set up by the Church Missionary Society. It was getting dark as the van bumped its way into the grounds, which are just below the cathedral.

SITE OF HORROR: Dan Wooding and Ray Barnett at Karuma Falls, Uganda, where thousands of bodies of the victims of Idi Amin’s terror machines were dumped to be eaten by the waiting crocodiles below.

“You are all most welcome,” said the ever-smiling manager, Naomi Gonahasa. We soon realised the incredible difficulties under which she and her staff were working. There was no running water and so it had to be brought in jerry cans from the city on the back of a bicycle, at $US1.50 a can.

Each resident was rationed to one bottle of brownish water per day – and that was for everything. They had no gas for cooking, so it was all done on a charcoal fire. What made it even more difficult was that there were no telephones working in the entire city, so we could not alert any of Ray’s contacts that we had arrived.

When we unpacked in the fading light, we heard the sounds of machine-gun fire reverberating across the city below us. Then came the sounds of heavy explosions and of screaming and wailing, which continued all through the night.

I now realised that Ray had been deadly serious when he told me that this trip could cost me my life. I got down by my bed and committed my life to the Lord.

“God,” I said against a background of screaming, “I don’t know what is going to happen here, but I want you to have your own way with my life, and that of Ray. We realise the dangers, but they are nothing to what our brothers and sisters here have faced over the past eight years.”

As I stood up, I turned to Ray who was calmly lying on his bed, reading his Bible, and said, “A fine mess you’ve got me into again”.

He smiled. “Where would you rather be – in Fleet Street, or here, serving the suffering church of Uganda?”

My look showed him that I knew I was now in the centre of God’s will.

During our stay at the guest house, we became firm friends with Naomi and her husband Stephen. As we built up trust with them, they revealed their part in saving the lives of believers on the run from Amin’s savage killers.

I learned from them the secret code word which they responded to when someone came to them for sanctuary.

“This was a good hiding place from State Research people,” said Stephen. “People would turn up here and as long as they knew the code word “Goodyear”, we would hide them. Their food was served in their rooms. Naturally we would not let them sign the guest register in case it would be checked.”

Naomi added, “We were not really frightened, because we believed that God was protecting us.”

This sincere young couple, obvious targets for the State Research, were also active members of an underground church. Often believers from the Deliverance Church, one of the twenty-seven groups banned by Amin after receiving orders from Allah in dreams, would have meetings in the lounge of the guest house.

Next morning we had our first experience of the terrible ferocity of Amin’s battle against the church during his reign of terror. We went to a church in Makerere, run by the Gospel Mission to Uganda. As we examined the bullet holes that had riddled the ceiling and the walls, I asked a member what had happened.

He told me that on April 12th, 1978, Amin’s wild-eyed soldiers had invaded the church and begun firing indiscriminately at the 600-strong congregation. Assistant pastor, Jotham Mutebi, was on the platform and he sank to his knees in prayer.

“At least 200 remained on their knees and continued to worship the Lord when the soldiers returned and continued spraying bullets everywhere.”

Amid the mayhem, hundreds more quickly dropped to their knees between the pews. With upraised arms they began to praise the Lord. The sturdy red brick church was filled with a cacophony of incredible sound – a combination of prayer, praise and bullets.

Joseph Nyakairu, a member of the church orchestra, raised his trumpet to his lips and blew it as loudly as he could. The Amin soldiers thought the Christians were about to counter-attack and fled the sanctuary.

In the ensuing confusion, nearly 400 people managed to slip away from the church. But at least 200 remained on their knees and continued to worship the Lord when the soldiers returned and continued spraying bullets everywhere. They took hold of Joseph’s trumpet and threw it to the ground, spraying bullets at it. Then they “executed” the organ. The congregation knew that death could be imminent and that they were under arrest!

They were taken to the State Research Bureau headquarters at Nakasero, and there they were mocked and told that as soon as General Mustafa Adrisi, Idi Amin’s second-in-command, signed the execution order, they would all be burned alive.

The 200 sat in silent prayer and even as they prayed, General Adrisi was involved in a terrible car crash in which both his legs were badly fractured. He ended up a cripple in a wheelchair and finally Amin turned against him,” said one believer.

When the signed order from Adrisi did not appear, the guards led the prisoners to the cells. They were kept behind bars for some months. Many of them were badly tortured, but miraculously none of them died.

As we left these incredible people, I turned to Ray and said, “I’ve never met believers of this caliber in my country. They certainly have much to teach us about faith and courage.”

We bumped along for hours on end, having to stop regularly at road blocks.

In Latim’s hometown of Gulu, we learned the astonishing story of the burial of Archbishop Janani Luwum, who according to credible sources in Kampala, had been brutally shot in the mouth by Idi Amin himself.

Mildred Brown, an English woman who was working in the region translating the Scriptures into Acholi for the Bible Society, began to explain how Janani’s body had been taken to his home village of Mucwini, near the Sudan border, for burial.

His mother, at her home, told the soldiers, “My son is a Christian. He cannot be buried here; he must be buried in the graveyard of the local church.”

So the soldiers took the coffin to the picturesque tiny hilltop church for a hurried burial.

As we drank our tea, Miss Brown told us, “The soldiers had begun to dig the grave, but hadn’t been able to complete the job before dark because the earth was too hard. They left the coffin in the church overnight so they could finish the grave the next day.”

“They were all gazing quietly, reverently, at the body of a martyr, a man who was killed for daring to stand up to the ‘black Hitler of Africa’.”

Thus the hardness of the ground gave the group of believers at Mucwini the chance to gaze for the last time on their martyred archbishop. By the flickering gleam of a hurricane lamp, they saw the body of a purple-clad man. They noted there were two gun wounds, one in his neck, where the bullet had apparently gone into his mouth and out again, the other in his groin. Janani’s purple robe was stained with blood, his arms were badly skinned, his rings had been stolen, and he was shoeless.

They were all gazing quietly, reverently, at the body of a martyr, a man who was killed for daring to stand up to the “black Hitler of Africa”.

Even as the people gave thanks for their beloved archbishop, just one of some 500,000 victims under Amin, the government-controlled newspaper, Voice of Uganda, published a call for President Amin to be made emperor and then proclaimed Son of God.

Our trip into the heart of Amin’s holocaust even took us into Karamoja, where naked men and boys would run across the track brandishing spears.

Famine was rife in that region. Our final memory of Karamoja was the old lady who was too weak to move, sitting silently in the village of Kotido. The woman, who appeared to be near death, squatted by her open hut to keep out of the sun’s rays. She said through an interpreter that she had eaten only wild greens for two months. She displayed large folds of loose skin around her rib cage. Famine, more than Idi Amin, had taken its toll in Karamoja.

Back in Kampala, we were able to meet up with “God’s Double Agent in the President’s Office”. Ben Oluka, who was senior assistant secretary in the Department of Religious Affairs in Amin’s office, had used his influence to bring about the saving of many Christian lives throughout Uganda.

But what Amin did not realise was that Ben Oluka was not only doing what he could to assist suffering believers, but was also pastoring an underground church in his home. It was a small group from the Deliverance Church, an indigenous Ugandan evangelical fellowship.

“At that time, I was working in the office that had to enforce the president’s ban (against the 27 denominations), and secretly I was running an underground church myself,” he said. “When the ban was announced, much of the church immediately went underground, and house meetings sprang up throughout the country. There is a higher power, and when government restricts freedom of worship, God’s supremacy has to take over. I was personally ready for martyrdom.”

And that was the feeling of millions of Ugandan believers, regardless of Amin’s persecution. They were willing to die for Christ.

At the end of the trip, I knelt by my bed at the Namirembe Guest House and prayed, “Lord, these Ugandan believers have had such an impact on me that I want to dedicate my talents for the rest of my life to helping suffering believers around the world who don’t have a voice. Please help me to be a voice for them.”

I returned from Uganda a different person. The courage of the Ugandan Christians will live with me forever.

“After working on a story like this, how can I ever return to Fleet Street?” I shared with my wife Norma back home in England.

Now, with the news of this new movie about Idi Amin, I realize how his persecution of his people and particularly the Christians there, had changed my life forever. What Amin meant for evil, God has used for good!

This article was first published on www.assistnews.net. Dan Wooding is the founder and international director of ASSIST (Aid to Special Saints in Strategic Times) and the ASSIST News Service (ANS). Now living in California, the award-winning journalist was, for 10 years, a commentator, on the UPI Radio Network in Washington, DC. Wooding is the author of some 42 books, the latest of which is his autobiography, From ‘Tabloid to Truth’, which is published by Theatron Books. To order a copy, go to www.fromtabloidtotruth.com.