CHRISTOPHER GILBERT, in a special long read, speaks with the “outback historian” Paul Roe about his passion for telling stories that shed light on little known aspects of the history of Christianity in some of the more remote parts of Australia…

In 1890, Presbyterian Minister Rev William Guthrie Spence made the township of Bourke in the Australian state of New South Wales the hub of a national shearer’s strike. Out of this uprising of the newly formed Australasian Shearers Union came the Australian Workers Union and, eventually, today’s Australian Labor Party. It’s a story much written about in various histories of Australia, but a key element is mostly absent: What was motivating Spence, a Christian minister, to organise people into labour unions? And what has that to do with an Australian identity?

University of New South Wales history graduate Paul Roe had no idea that one day he would be handling hundreds of such outback stories and finding answers to important questions of people and places that Australian historians hadn’t previously considered. His journey began against the tide of urban drift, and took him from his city home to shearer’s quarters on a cotton farm to the west of Bourke in outback New South Wales. With his wife Robyn, he left the Sydney suburb of Epping in 1976 and, via a year of study in Vancouver, Canada, returned to Australia to land at Fort Bourke Station early in 1978. They spent the next 20 years there.

Paul Roe standing by the Darling River in Bourke. PICTURE: Supplied

It was what Paul Roe found at Fort Bourke Station that, he says, kept them there: Australian characters of every kind, with hidden stories of extraordinary contributions to Australian life. Their achievements and their mistakes; their virtues and their vices. Story gems he was given in trust by people in places overlooked. And, concerning the township of Bourke – the gateway to the outback, he tells of the transformation of dignity and new beginnings that publishing those stories brought to a community previously known for its racial strife. It also brought new focus and direction to his own life as an evangelical Christian along with a project of national significance.

“I’ve got my antenna out for stories all the time,” says Roe, via Zoom from his current home in Dubbo. “My daughter-in-law grew up in Darlington Point [south central New South Wales]. Right across the road from where she grew up, the Anglican church there, it was begun by the Reverend John Gribble in 1879. He built a mission there for the Indigenous people called Warangesdah. He was very feisty, [a] bit of a maverick type of person. He built it with his son, and I read somewhere that it was the only safe place in New South Wales at that time for Indigenous people. But out of that mission came a significant figure, a guy called Bill Ferguson who has been memorialised here in Dubbo as, well. I call him the Martin Luther King of Australia. He kind of led the civil rights movement [in Australia] starting in Dubbo.”

“The surface story of Australia is secular but the subterranean story is Christian…”

– Paul Roe

Roe sees himself as “making the invisible story visible”, a quote he borrows from historian Stuart Piggin.

“The surface story of Australia is secular,” Roe says, “but the subterranean story is Christian, and Piggin [with Linder] has detailed that in his two big volumes [The Fountain of Public Prosperity and Attending to the National Soul] published in the last couple of years to critical acclaim.”

Roe believes the church – which he says has under-valued Australian history and doesn’t know its own stories – must share the blame for “allowing reigning secularism to bully us into silence”.

A lameness has crept into churches thanks to the paedophilia scandal and some chapters of Indigenous history, he says, “but we feel the pain of those failures too. And they’re only a part of the story of Christianity in Australia.”

Roe says Piggin has tried to rectify the general tendency of popular media and the universities to edit out the Christian influence in our history. He also acknowledges Meredith Lake’s The Bible in Australia, which won the Prime Minister’s award and New South Wales Premier’s Award, for also correcting the record and re-interpreting who we are as Australians.

For himself, Roe is collecting the stories in all sorts of small corners of Australia which reveal “Jesus’ footprints are all over this country”. His own book, a memoir on his lifetime pursuit of stories, is finished but not yet titled, and will be published later this year.

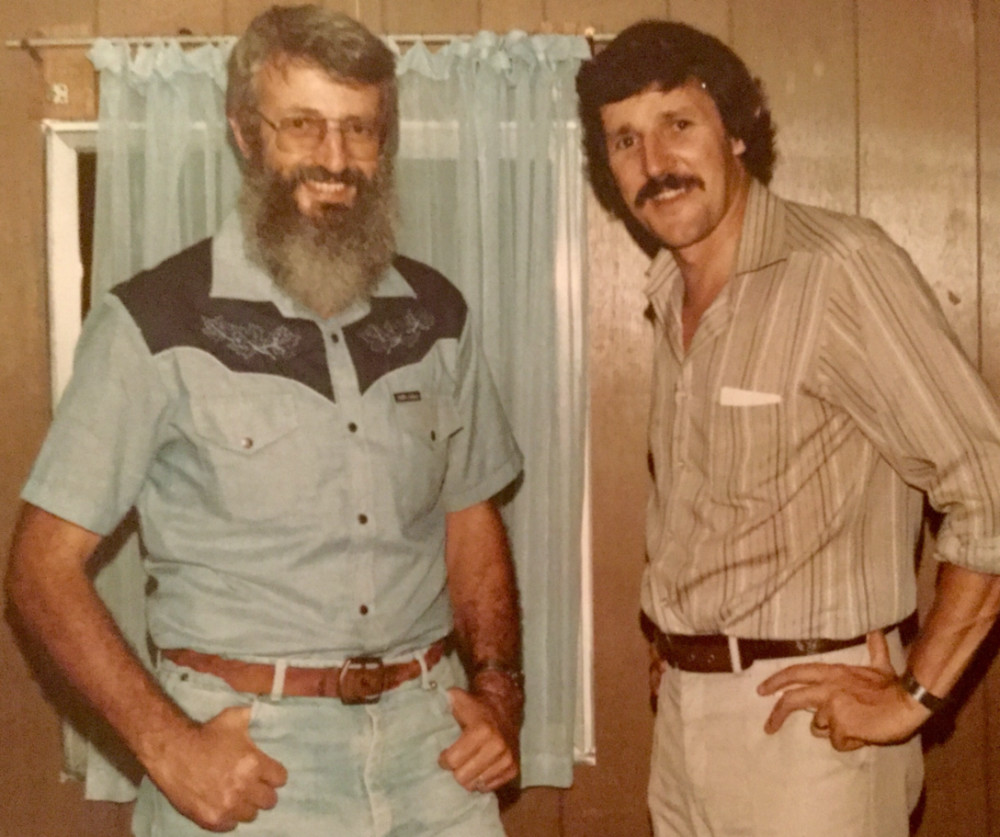

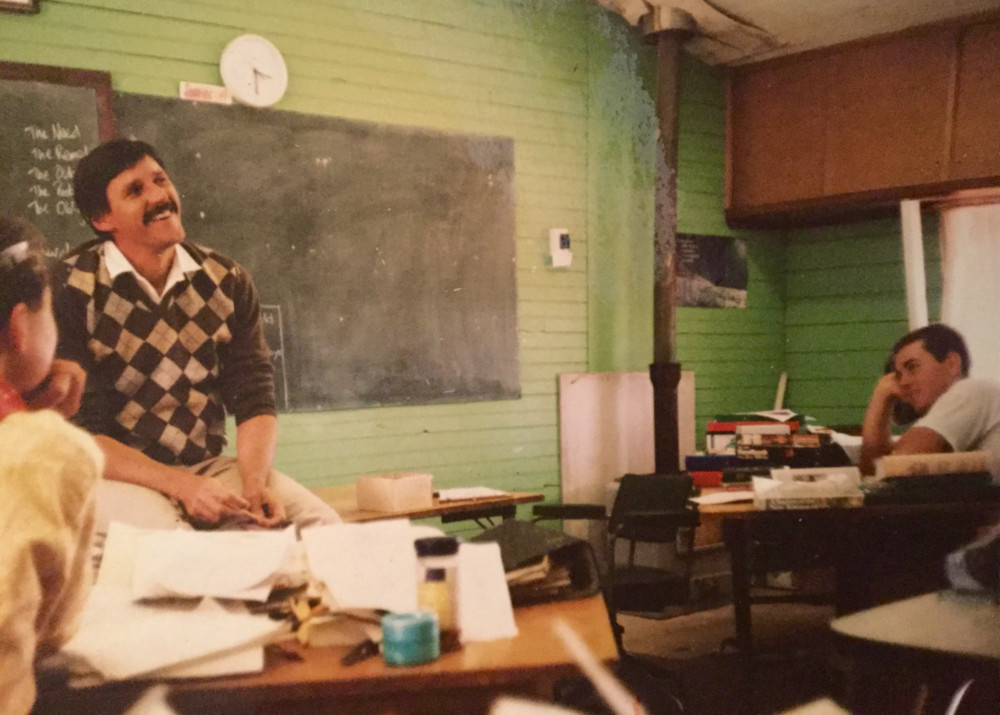

Top – Paul Roe (right) with Laurie McIntosh, 1978; Middle – At the Pera Bore School House Cornerstone, circa 1980; Bottom – Paul Roe at 2WEB, circa 1979. ALL PICTURES: Supplied.

Spiritual pilgrimage becomes bush apprenticeship

“When I was at university I came under fire from a very hostile professor,” Roe recounts. “He picked me out in the first seminar and said, ‘Are you a Christian?’ I said ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘I thought we worked that nonsense out of you in first year.’ He was good for me because he put a blowtorch on my faith and made me defend what I believed, not just quote Bible verses.”

Roe then met Laurie McIntosh who was helping his brother establish a dairy farm on the Darling River in Bourke. McIntosh had begun adult life as an atheist, trained as anthropologist, and, by the 1970’s, had returned to Australia from some years in the jungles of Mexico as a Wycliff Bible translator and as a university campus evangelist in the UK.

“He had a rigorous faith, would go into the public square and debate it,” says Roe. “He was good for me.”

Roe spent five years learning from McIntosh in the context of university ministry as well as church youth work before they dreamed up Cornerstone Community, a school for Christian discipleship training based at Fort Bourke Station on the Wanaaring Road, 15 kilometres west of Bourke.

“We wanted young people to really ‘take life deep’, an expression we used then, to give young people a chance to really unpack their faith, to know why they believed it.”

But the Lo-debar dairy (the Hebrew means “no pasture”) seemed a most unlikely place to be planning this for Roe, and he mimicked the Apostle Nathanael in John 1:46 saying, “Can any good thing come out of Bourke?”

In 1976, Paul and Robyn Roe departed to Regent College in Vancouver for some theological training. By 1978, the Roes and two families of McIntoshes had established Cornerstone Community with the assistance of two expatriate families from the US. It was something like an Aussie kibbutz on pioneer cotton farms with a first year intake of 12 students.

“In our hearts we really wanted to put the Christian faith in a tough Australian setting,” says Roe. “I realised in Canada I knew very little of the Christian story of Australia and I felt sad about that. So when I came back I started this journey of trying to find out what made Australians what we were, the part that Christianity actually played.”

Three turning points

Roe’s first challenge was how to teach the Bible to seasoned bush sceptics. Local access radio 2WEB sharpened his education in connecting with his audience. He began with what he felt was a winsome half-hour program on the story of Jesus, he recalls, laughing while recounting it. It was just one of a smorgasbord of local programs including news from the BBC, Bach chorales, local reporting and stories of local kids, local schools, local sports and so on. But then he was asked to collect oral histories from the region’s old timers before they passed, and create the program called Bourke and Beyond.

“It’s one thing to learn history at a university but it’s another thing to sit down with a veteran from World War I, or a bloke who’s ridden a border fence for 50 years or a lady who was married to an Afghan cameleer, and hear their stories,” he muses.

Roe’s job at 2WEB was to give the stories a context, edit and deliver them to the people of the district and he collected more than 100.

“It felt like a sacred trust, them putting their stories in my hands,” he says. “Ian Cole, the radio station manager, said to me, ‘Since you’ve been doing this oral history you’ve got far more entry into the community than just doing the religious program.’”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

{subscriber-ad}

A few years later, on a “Poet’s Trek” to Hungerford that Roe initiated, another historian took Roe aside for a heart-to-heart.

“He said, ‘Mate, when you first came to town you were talking at us. Now you’re talking with us,’” Roe recalls, “Which was quite an insight for me.”

He continues: “Evangelicals in particular are prone to gallop into town with a white hat on to say ‘We are here to fix things, now shut up, sit down and listen’. But I learned that I first had to listen to their stories. And it was an honour. I was actually handling the stuff of Australian history, live.”

Roe discovered that many of the stories were not only of national significance but they also revealed the sincere Christian faith of the characters in all their complexity. Like Presbyterian minister, WG Spence.

“His only aim was to show the men that Jesus cared about them,” says Roe.

Opposed to Spence as initiator of the Pastoralists Union was another Presbyterian, Sam McCaughy, whose pioneering use of mechanical shears on Dunlop Station in Queensland provoked the shearer’s strike. McCaughy was a brilliant inventor, instrumental in engineering the Murrumbidgee irrigation scheme, and owned three-and-a-half million acres of land, shearing a quarter of a million sheep. His early 20th century philanthropy saw him invest his amassed pastoral fortune into a trust at his death for funding hospitals, higher education, and churches across Australia. The trust continues that philanthropy today.

“Here’s these two men of faith on quite opposite sides of the fence in Bourke, but big things were afoot, things that shaped the country,” Roe explains. “I began to see, ‘Wow, there are stories of faith here that nobody knows’. It began to open my eyes to the fact of subterranean stories that were being overlooked – or edited probably – and we Christians were probably mainly to blame because we didn’t know our own stories and didn’t really value them. But Jesus said ‘Put your lamp right up on a hill, do your works so men will see them and glorify the Father in Heaven’. So He said broadcast it! That gave me a warrant. So I began to think how can we re-introduce these stories into the bloodstream of the country; they belong to us all. It’s our shared story, our DNA.”

Roe says if we don’t know why John Flynn began the Flying Doctor Service, or why Stanley Drummond began the Far West Children’s Scheme or why WG Spence began the union, we won’t really understand ourselves. And so he became fascinated with strategies of storytelling.

“I watched a lot of really good story-tellers in Bourke, yarn spinners and so on,” he laughs. “They taught me a lot, and the fun of it.”

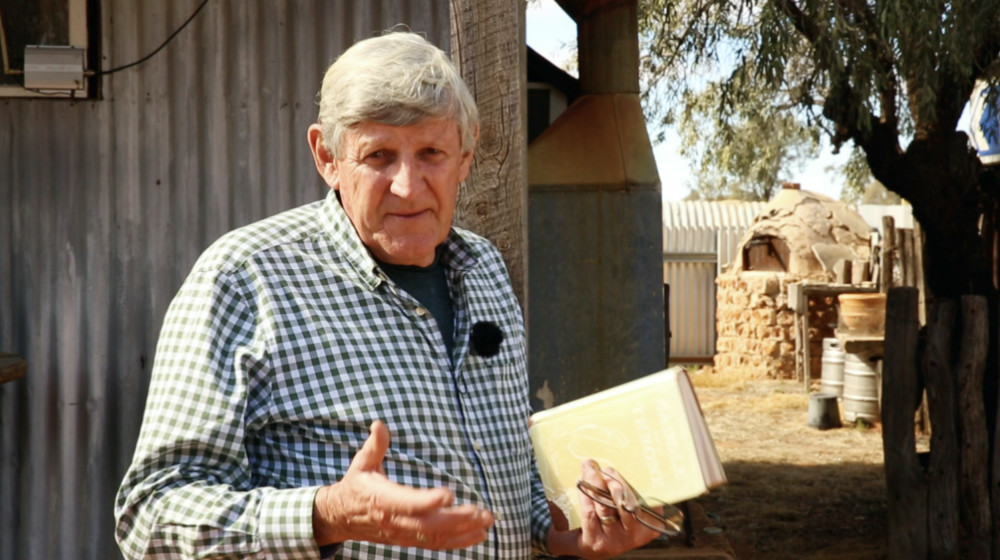

Paul Roe at Toorale Station, about 80 kilometres west of Bourke. PICTURE: Supplied.

It was on a trip to Scotland that Roe came across a story-telling centre in Edinburgh, which posted a local saying: “Storytelling is eye-to-eye, mind-to-mind and heart-to-heart”. The footnote attached to it read: “We need to release children from the solitary confinement of the screen”.

As a storyteller working from Bourke’s newly constructed tourist centre, Roe found it natural to take tourists for bus rides and tell the stories he’d been given in the same way. In a blank spot at the end of a tour he would say to them, “I think there’s a bigger story afoot here. We all need to find our place in God’s big story.”

“Most would go very quiet and be looking out the window,” he explains. “But almost without exception they’d applaud, often with words of thanks to say as they left the bus.”

That’s when Paul Roe found another turn in the road.

He’d once taught children at the Pera Bore school on Fort Bourke Station about three outback poets: Henry Lawson, Breaker Morant and Will Olgivie. To make the poetry live, he organised a “trek” in their footsteps. The “trek” was from Bourke to Hungerford and the kids would get to read the poems exactly where they’d been written. He turned that experience into a regular “Poet’s Trek” that was conducted for about 20 years before it became a documentary.

“On that trek I learned another thing,” he emphasises, “The power of connecting story to place. If you go to a place and tell a story to people on location it has a deeper magic. They could walk or drive through that place and not see it. But when you’ve got an interpreter that’s when, suddenly, it leaps into focus. It’s engaging people’s heart with their own heart music.”

Roe recalls the impact the trek had on three people who took it. A sceptical lawyer pressed him for an explanation for her intuition that on the trek “there was something going on” and discovered that Lawson’s walk to Hungerford was affecting her like a parable, asking questions of her own search for meaning. A retired professor of Australian poetry experienced “the magic” in being on location and went home to write another book. And, for one young man, the experience led to an outpouring of poetry and music, and so Andrew Hull later became known as the ‘bard of Bourke‘.

Paul Roe on location at Breaker Morants hut on Sharron Station filming the ‘Poets Trek’. PICTURE: Supplied.

The impact that Paul Roe is most grateful for is the impact on the town of Bourke itself.

“When I was on the local shire council we did a town audit and what struck me was that one of the great assets that Bourke people realised they had was their stories. But people could drive into town and they’d just see the war zone,” he says with a grimace, referring to the 1970s and 1980s when there was visible conflict between Aboriginal people, white business people, and police. Businesses on the main used roller shutters, often graffitied, to protect their wares and drunken violence and the presence of police would cause visitors to drive on.

Wiradjuri man Victor Bartley (front, right) is a councillor on the Bourke Shire Council. PICTURE: The Western Herald

“The Back O’ Bourke Centre has attracted tourists. Maybe I’m biased, but it’s as good as anything around the country. It’s got a lot of Indigenous things there supplied by the indigenous people. A lot of people involved. The white community really appreciate what we’ve got here now. We’ve got somewhere you can go along and look at our past and look at our present. I’m proud to say I’m a Bourkite.”

– Victor Bartley, a Wiradjuri man and Bourke Shire councillor.

Roe thought there might be a role he could play and began with the tourism centre idea, developing all sorts of story-based tourism walks, drives and river trips.

While trying to get an “interpretive centre together” he says others chided him: “Nah a waste of time mate, you’ve got to fix the problems first.”

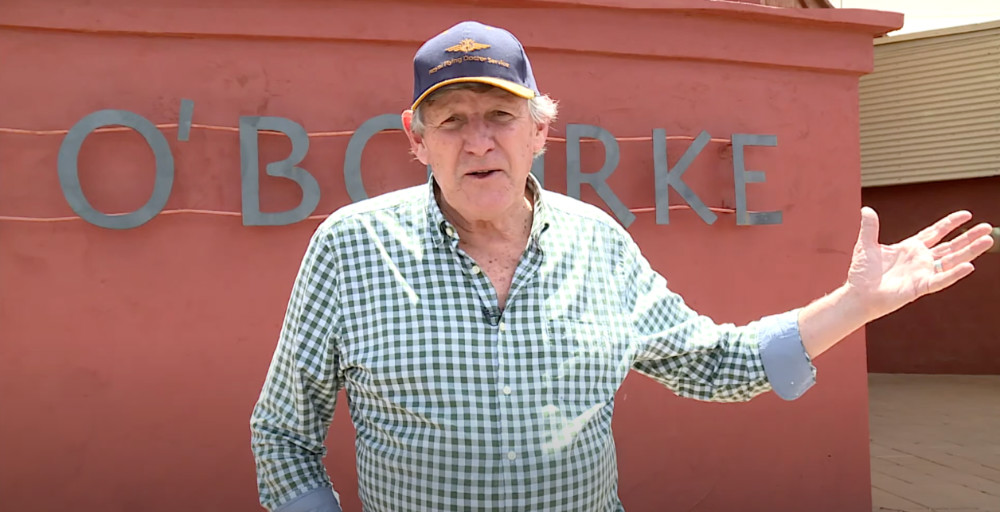

“I responded, well, maybe this is part of the answer: to give people a sense of who they are,” he says. “That was a long journey, 10 years in the making but we ended up with the Back O’ Bourke Exhibition Centre, an $A8 million dollar story-telling apparatus.”

Shire councillor, Ian Cole, is Bourke born-and-bred. Reflecting on the changes for the town he says: ”It’s given it first class facilities but I think it’s much more than that. It’s given Bourke a far deeper realisation of its roots and its history and its heritage.”

“You know, I grew up here through school and didn’t know about [Darling River] paddle steamers, fair dinkum. I knew about the submarines in Sydney and the Sydney ferries and could tell you about the rivers of coastal New South Wales from top to bottom, but I couldn’t tell you anything about Bourke’s history. It’s taken someone like Paul to come along and bring them to life and articulate them through the tourist centre, on 2WEB, and writing them in the paper.”

Wiradjuri man Victor Bartley is also a councillor on the Bourke Shire Council.

“The Back O’ Bourke Centre has attracted tourists. Maybe I’m biased, but it’s as good as anything around the country,” he says. “It’s got a lot of Indigenous things there supplied by the Indigenous people. A lot of people involved. The white community really appreciate what we’ve got here now. We’ve got somewhere you can go along and look at our past and look at our present. I’m proud to say I’m a Bourkite.”

Roe reflects on this: “As we focused the stories and articulated them on radio, people began to write books and music, artists began to paint paintings. The stories had a regenerative affect on the district. Russell Mansell built a beautiful riverboat, people began to tell their story on their farms, businesses improved their appearances. I felt that was a Kingdom of God effect. And a lot of Christian people were proactive in making it all happen.”

Paul Roe in front of the Back O’Bourke Exhibition Centre. PICTURE: Supplied.

Envisioning a national interpretive centre for Canberra

“Well, out of that I began dreaming of doing the same thing in Canberra,” Roe continues.

In 2006 Stuart Piggin and others called a conference of people together in Parliament House, Canberra, for a two day congress about Australia’s Christian heritage. Roe was inspired. The challenge was to make the stories visible. In the process, he completed a PhD around the importance of story for a nation.

“We began plotting to set up a story-telling apparatus a la the Back O’ Bourke Centre that was going to articulate this history on a national level. And, for the first time, to gather our stories into one place because they were all tucked away in small corners,” says Roe.

He explains why by comparing the myth-making power of the Australian War Memorial which has kept the ANZAC story alive for over 100 years.

“I love it as much as anybody,” says Roe, “but what struck me was, does it really qualify as our national myth?” He points to its subject, war, on locations overseas, mostly about men, at great cost to our country as a narrow story in some ways.

“Our Christian story – if you add it all together and articulated it – is a much broader, longer, higher, story to tell,” he suggests. “Although we take a 100,000 kids a year through the War Memorial and we expound the ANZAC values to them, my question is where did the ANZAC values come from? Did they just spring to life at Gallipoli or on some other battlefield, or did they come from the New Testaments the government gave them that they carried in their pockets? And what about the Sunday schools they all went to? But we tend to turn the ANZACS into secular saints.”

Roe and others working to realise this Canberra project, simply want to take a more sober look at the ANZAC story, its strengths and weaknesses. They hope to build a stunningly beautiful Australian story interpretive centre as a national institution like the War Memorial to multiply the impact for good already experienced in Bourke, only this time for all Australians. After more than 10 years in the planning, Roe says much remains to be understood and done before it might become a reality.

So what drives a man in his 70s to take on such a huge project and regular outback pilgrimages? Paul Roe is clear that he wants the stories in the hands of an army of story-tellers, history teachers, teachers in Christian schools, broadcasters, documentary makers, troubadours, artists.

He says, education departments say they’re interested in any valid Australian stories being embedded into school curricula.

“The one’s I’ve told you for example, the beginning of the union movement, if you were an honest historian you’d say WG Spence did what he did because, as he said, he wanted to show how the Gospel worked for the working man,” Roe explains again. “Why did John Flynn begin the Flying Doctor Service? Well, he said because Jesus inspired him. And so I say, the stories give us warrant to remind Australia of its Christian story.”