There have been many Christian Prime Ministers in Australia’s history. But for the first time, a Pentecostal Christian holds that office, prompting a greater-than-usual level of public interest in the PM’s faith. DAVID ADAMS reports…

On the same day Scott Morrison was sworn in as the 30th Prime Minister of Australia – 24th August – following his sudden elevation to the office, the stories about his Pentecostal Christian faith began appearing in the media, both in Australia and overseas.

Since then, there have appeared numerous examinations of the Pentecostal denomination, explorations of how the Prime Minister’s faith might impact his decisions and interviews with pastors from the church he and his family attend – Horizon Church in Sydney’s Sutherland Shire. And when, just last weekend, the Prime Minister prayed at a Melbourne church for those affected by the earthquake and tsunami on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi (and was filmed doing so), that became news as well.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison (right) meeting with Indonesian President Joko Widodo on the new PM’s first trip overseas after taking up the office on 24th August. PICTURE: Timothy Tobing/DFAT (licensed under CC BY 2.0)

“I think there’s been greater interest in Scott Morrison’s faith than we usually see in discussions around the Prime Minister.”

– Simon Smart, executive director of the Centre for Public Christianity.

While, to be sure, it’s not the first time Australia has had a Christian Prime Minister – Kevin Rudd and Tony Abbott are two other recent Prime Ministers whose faith was up for discussion at least to some degree, commentators spoken to by Sight say that the media’s fascination with Morrison’s faith does seem to be at another level.

“I think there’s been greater interest in Scott Morrison’s faith than we usually see in discussions around the Prime Minister,” says Simon Smart, executive director of the Centre for Public Christianity.

He notes that while it’s true most recent Prime Ministers have professed a Christian faith of some form or other – with the notable exception of self-confessed atheist Julia Gillard, he suspects the interest comes with the fact that he’s the first Pentecostal Prime Minister, a denomination which represents something of an unknown to many people.

“This does appear to spook some people – they’re at least intrigued by it and unsure of it and therefore wanting to talk about it,” says Smart, noting that most media reports about Pentecostalism show it to have “ecstatic forms of worship and not much else”.

“It might be that they’re suspicious of that brand of faith, partly because it’s less familiar, whereas some of the more established traditions might appear safer to them.”

John Warhurst, emeritus professor of political science at Australian National University, says that as well as the fact that Morrison is a Pentecostal Christian – which attracts “a particular sort of interest, curiosity almost in some quarters”, he believes the focus on Morrison’s faith is part of a broader trend.

“It’s very interesting that it’s probably in recent years, more than any earlier time, that a lot has been made about Prime Ministerial religious belief. In some ways, a little bit was made of Bob Hawke’s agnosticism and Julia Gillard’s atheism so in one way or another religious belief, or lack of it, can attract attention.

“I think in Scott Morrison’s case, it’s partly a consequence of the build-up in recent years of interest in religion. In a perverse sort of sense, I think the fact that religious belief in the general community is usually described as declining makes it perhaps all the more interesting that you have a Prime Minister with considerable Christian religious beliefs.”

Australia’s Parliament House. PICTURE: Jason Tong (licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Morrison certainly hasn’t been shy about speaking about his faith – it was an integral part of his maiden speech to Parliament, delivered on 14th February, 2008, when he talked about growing up in a Christian home, thanked numerous pastors – including Hillsong’s Brian Houston and Leigh Cameron – for the part they played in his life, and quoted Desmond Tutu in explaining what is expected of a Christian. He has also alluded to it numerous times during his political career since, including after becoming Prime Minister.

“You can’t understand ScoMo without understanding his faith…” points out Gary Bouma, professor emeritus of sociology at Monash University. “It is a critical part of his identity and he has made it so but it always has been there…”

(Bouma, incidentally, points out that based on the latest Census data in Australia, there are now more Pentecostals in the nation than there are members of the Uniting Church, an analysis he bases on the number of people who define themselves as Pentecostal added to the number of people who see themselves as Christians but won’t define themselves further – a group he says includes Hillsong and churches under the Australian Christian Churches umbrella).

Martyn Iles, managing director of the Australian Christian Lobby, says it’s been a “long time” since there was a Prime Minister with a faith as “overt” as Scott Morrison’s.

“He is not only a conscientious church-going Christian from a church-going family which has church involvement but also…he is very happy to speak about his faith publicly, he handles questions on it without taking a backward step and it has become clear through his politics over the last few years that his faith does impact his politics.”

“He is not only a conscientious church-going Christian from a church-going family which has church involvement but also…he is very happy to speak about his faith publicly, he handles questions on it without taking a backward step and it has become clear through his politics over the last few years that his faith does impact his politics.”

– Martyn Iles, managing director of the Australian Christian Lobby.

And yet Morrison has also famously said – when coming under fire for the Coalition’s “stop the boats” policy that he doesn’t see the Bible as a “policy handbook” – a comment generally interpreted as an attempt to reassure voters that his faith won’t trump his political values.

Asked about that quote, Iles says it’s true the Bible doesn’t contain a “list of policies for a democratic, modern Australian Government to implement”. But he adds that it does contain “very important principles which should inform the way a government operates and the way policies are formulated”. His hope is that a “deeper analysis” of Morrison’s comments would reveal a “respect” for these principles.

“[T]o have that consciousness certainly has a big impact on how somebody acts politically. Now, nobody’s perfect and people err, but also people have different understandings of particular details so I would never hold Scott Morrison up as a perfect example or put that pressure on him to be a perfect example but certainly I think that we can expect somebody who takes the principles of his faith seriously in so far as they translate into every sphere of his life, including his work.”

Some commentators spoken to by Sight say that talking about one’s faith in politics can be a dangerous game with the charge of hypocrisy ever present.

“It’s understandable why they’re a bit cautious to be very overt about their faith,” says Smart. “Because it rightly puts them under more scrutiny to live up to that faith. Lots of them will say they don’t feel comfortable being judged on that kind of measure.”

Warhurst says that certainly those politicians who are very “out there” about there beliefs can run the risk of being called hypocrites, citing, for example, the criticism former Prime Minister Tony Abbott received from some Catholics over his stance on asylum seekers and refugees.

“And that, I don’t think, was ever properly fully resolved. I think his position – which he had to explain eventually – was ‘I’m a politician and I have to hear all views in the community and anyway, I’m not going to directly translate my religious faith into policy positions’.”

“Generally, I think, you’ll find that it’s not all or nothing and Scott Morrison might satisfy those in the Pentecostal and other similar communities who expect a lot of him – he’ll satisfy them in some areas and in other areas, he just won’t be able to satisfy them. And I think he’s probably conscious of that…”

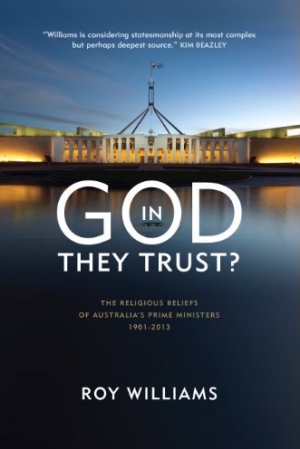

Roy Williams – author of In God They Trust? The Religious Beliefs of Australia’s Prime Ministers 1901-2013, says that while he has no problem with the fact Morrison cited people like Abraham Lincoln and Desmond Tutu in his maiden speech, “if you’re going to say those things, you can expect to be held to that standard”.

“Christianity sets a very, very difficult standard for anyone in politics to meet because, essentially, what I’d call authentic Christianity is now antithetical to key beliefs on both sides of politics…The Right’s got major problems and the Left’s got major problems with certain aspects of Christianity. As a whole package, it simply doesn’t fit into ALP or Liberal Party philosophy, if it ever did, but it certainly doesn’t any more.”

– Roy Williams, author of In God They Trust?

“And on a number of things, Morrison’s record just does not stack up against the standard he set himself,” he said. “But…Christianity sets a very, very difficult standard for anyone in politics to meet because, essentially, what I’d call authentic Christianity is now antithetical to key beliefs on both sides of politics…The Right’s got major problems and the Left’s got major problems with certain aspects of Christianity. As a whole package, it simply doesn’t fit into ALP or Liberal Party philosophy, if it ever did, but it certainly doesn’t any more.”

While in the past, Williams – who notes that as well as being the first Pentecostal, Morrison is also “arguably the first evangelical”, a term he defines as someone who has a reverence for the Bible “as the written Word of God” and who see evangelism as a “duty” – says the evangelical vote in Australia largely went to the Liberal Party, that changed with Kevin Rudd in the 2007 election when Rudd deliberately went after the Christian vote.

Which he did, in a win which has been partly attributed to the so-called “Bonhoeffer effect” – a reference to the idea that Rudd’s projection of himself as an active Christian convinced some normally conservative voters in Queensland to vote for the ALP.

“It appears he ate into that evangelical vote very substantially,” Williams says. “But Labor’s probably lost it again.”

One issue that Morrison has been speaking about since taking office as PM has been religious freedom, talk which comes against the backdrop of a government inquiry led by former Attorney-General Philip Ruddock into the issue which was sparked after the vote on same-sex marriage last year.

Williams says, in a sense, Morrison has been fortunate given that religious freedom, a hot-button issue at the moment in Australia, is one which resonates with Christians of all persuasions.

“It’s hard to see how a fair dinkum Christian of whatever stripe would disagree with the concept of embedding rights of religious freedom into law…” he says. “At least in terms of the Christian vote he’s trying to pitch to, I think it’ll be a winner for him. He may lose other votes, he may further antagonise other voters but at least among Christians I don’t see it as being a divisive issue.”

Faith-based education – and his opposition to some of the gender-based programs in schools, the influence of what he recently called “gender whisperers” – is another issue that Morrison’s already waded into which will resonate with some Christians in the community but it’s not just Morrison who seems to be bringing his faith into his politics. Christian groups, too, have seen Morrison’s elevation to the Prime Ministership as a chance to appeal directly to his faith in addressing specific issues.

“[Some] parts of the Christian community are appealing to him specifically to…bring his faith to issues around refugee and asylum seeker policy which they feel is in disharmony with his Christian convictions,” notes Smart.

“He’s famously the architect of the ‘Stop the Boats’ policy which has been effective but many people would critique that as quite a brutal policy that doesn’t line up with the heart of the Christian faith which can be characterised by grace, mercy and kindness for the stranger and care for the vulnerable and the weak. Now this is a very complex area and people on both sides of politics have not, in my estimation, been able to come up with a good solution to it but it is an area that’s awkward when it comes to what has to be a complicated mix of conviction and the compromise of politics.”

“[Some] parts of the Christian community are appealing to him specifically to…bring his faith to issues around refugee and asylum seeker policy which they feel is in disharmony with his Christian convictions.”

– Simon Smart

Among the stories have appeared in the wake of Morrison’s taking up the office of Prime Minister has been a report in The Guardian quoting one Pentecostal pastor as stating that “darkness” would spread across Australia if Morrison doesn’t win the next election.

Most commentators spoken to by Sight suggest that such comments are not helpful to the Prime Minister. Roy Williams says that idea that God will bring darkness on the land if Morrison isn’t re-elected is an “insult to any non-Coalition voting Christian”.

“With friends like that, he might be on tricky ground because that will just get their hackles up,” he says.

At the end of the day, Smart believes that Morrison’s faith shouldn’t be seen as a threat to democracy.

He says that while he understands people who worry about religious people imposing their views, there have also been some “alarmist and over-the-top” responses – perhaps driven by the “disastrous” marrying of political ideology with religion which has been seen in the US – to Scott Morrison’s faith.

In a opinion piece published by the ABC in mid-September, he argued that the “public square should not be devoid of religion and religious voices” and “Scott Morrison should be as welcome as the next person to bring his belief system to the perilous dance between compromise and conviction that is modern party politics”.

He added that while Morrison was, to date, “most famed for a brutally utilitarian border protection policy that many of his fellow Christians are urging him to adjust, particularly the long-term detention of children”, a pressing question for him now “will be what aspect of his Christian conviction he hopes to be remembered for.”

That question is yet to be answered.

Clarification: The words “does not” were accidentally omitted from a quote by Roy Williams and have been added back in.