In an article first published on The Conversation, UK academics MARTA FAVARA, ALAN SÁNCHEZ, CATHERINE PORTER and DOUGLAS SCOTT report on the findings of a poll of 10,000 young people…

For many young people around the world, the economic effects of lockdown policies have been more significant than the health impacts of coronavirus. Young people are going hungry, facing widespread job losses or suspension without pay, and severely disrupted education, according to the results of a new phone survey of 19-year-olds and 25-year-olds in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam.

The phone survey was part of our Young Lives project, which has been following young people born in poverty in these four countries since 2001 to investigate the drivers and impacts of child poverty. We interviewed just under 10,000 young people between June and July about their experiences of COVID-19 and lockdowns in their countries. We found high levels of anxiety about the current situation.

Watering plants in Ethioipa: how young lives have been affected by COVID-19. PICTURE: © Young Lives / Mulugeta Gebrekidan

Hunger and help

So far, the health impact of the crisis has been higher in Peru and India than in Ethiopia and Vietnam. In Peru, around four per cent of the young people who were surveyed said they had been infected, compared to two per cent of the respondents in India (based in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana) and less than one per cent in both Ethiopia and Vietnam. In both Peru and India, around six per cent of the young people also believed someone in their household had been infected, but only around one in three said the person had been tested for the virus.

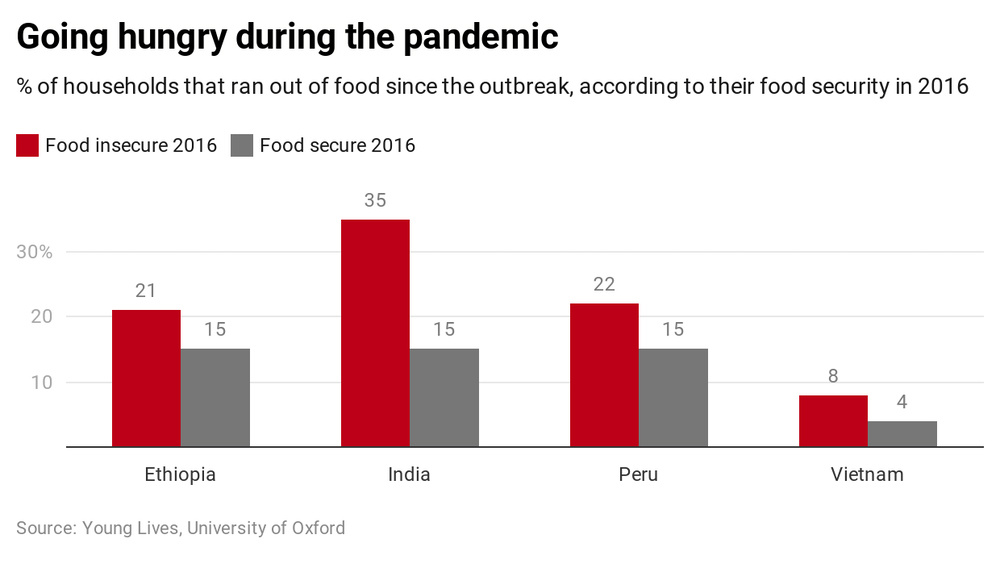

The crisis had less of an impact on food security in Vietnam than in the other countries. One in six of the households we surveyed in Peru, India and Ethiopia ran out of food at some point since the beginning of the crisis. This percentage was even larger among households that faced food shortages in our last visit in 2016 – and about twice as high in India. In Vietnam, the proportion experiencing food insecurity was much lower at four per cent.

Our respondents received varying degrees of government assistance. In India, more than 90 per cent of households received at least one form of support from the government during the lockdown, although in many cases the support consisted of a small basket of food or face masks. This compared to around half of those in Peru, falling to just 6% in Ethiopia.

In all the countries, support was relatively well targeted, reaching proportionately more of those households that reported food insecurity during the crisis. However, in Peru, despite every vulnerable household being eligible for a direct cash transfer, only 42 per cent of those we surveyed received one. This could signal either a targeting problem, a delay in payments, or both.

Job losses or suspension without pay are widespread even in Vietnam – the country least-affected by the virus – and remote working is the exception rather than the rule. Across the four countries, many of our 25-year-old respondents lost their jobs, and informal workers with no written contract were particularly severely affected. In Peru and India, seven out of ten respondents had reduced or lost their source of income due to lockdown, six in ten in Vietnam and four in ten in Ethiopia.

The proportion of those who lost income or employment was higher in urban areas than rural areas, and overall more men were affected by these losses. Remote working has been possible only for a minority of 25-year-old workers living in urban areas. In India, 28 per cent of those we surveyed said they were able to work from home during the outbreak, falling to 20 per cent in Vietnam, 18 per cent in Ethiopia and 17 per cent in Peru. We found the percentage was much higher for those living in households better equipped to take protective measures against coronavirus, presumably due to better access to the internet and the nature of the work undertaken.

Less learning, more caring

With schools and universities closed very early on in the outbreak in all four countries, the interruption to education was striking. But some were more likely to have their studies interrupted than others. Access to study from home was slightly higher for women than men in all countries, and wealth and parental education almost doubled the chances of being able to study at home.

In Vietnam, almost 90 per cent of the 19-year-old cohort accessed remote learning, falling to 70 per cent in Peru, and 38 per cent in India. In contrast, only 28 per cent in Ethiopia continued to learn remotely, and this fell to 14 per cent if their parents had no education.

Although slightly more 19-year-old women have been able to continue their studies online than men, wide disparities emerged in caring responsibilities. In all countries except Peru, more than double the number of young women than men have had to take on extra caring responsibilities during the lockdown. The disparity is particularly striking in India and Ethiopia.

Levels of anxiety about the current situation are high, especially in India. We asked our young respondents whether the statement “I am nervous when I think about current circumstances” applies to them. We found stress levels were worryingly high – in India over 90 per cent of respondents said the statement applied or strongly applied to them. In Vietnam and Ethiopia, 65 per cent agreed with the statement. Peru had the lowest anxiety levels, despite being relatively worse affected, with just under 50 per cent of respondents feeling nervous.

We’re now conducting a second phone survey asking for more detail about these young people’s employment experiences and how the crisis is affecting their working life, home life and education.![]()

Marta Favara is deputy director or Young Lives at Work and senior researcher at the University of Oxford; Alan Sánchez is principal investigator,of Young Lives Peru, a senior researcher at GRADE and an academic visitor at the University of Oxford; Catherine Porter is senior lecturer in economics at Lancaster University, and Douglas Scott, is a quantitative research officer in Young Lives at the University of Oxford. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.