EDUARDO CAMPOS LIMA reports on hopes among proponents of Liberation Theology that dialogue can be re-established with neo-Pentecostal churches, many of whom are key supporters of President Jair Bolsonaro…

Sao Paulo, Brazil

A recent survey showed that the far-right President Jair Bolsonaro’s approval rating has declined since April but still amounts to one-third of the Brazilian people. His resilience is particularly notable among evangelicals – 48 per cent of them approve of his administration. Yet only a few decades ago, such a scenario would have seemed impossible. In 1980, for instance, 89 per cent of the Brazilians were Roman Catholic – and many of them were influenced by a progressive Catholic movement.

As many specialists in religion studies currently debate the reasons for such a fast transformation and worry about the politicisation of faith under Bolsonaro, there seems to be a renewed interest in Liberation Theology, the most important liberal religious phenomenon in Brazil in the second half of the 20th century and which, until recently, used to inspire large portions of the population.

A church steeple in the skyline of the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil. PICTURE:

A new wave of Liberation Theology studies has gained editorial attention in the past few years and a great part of such intellectual output has attempted to explain the religious transformations in Brazil in the last decades. Some studies focus on possible ways to reconnect with the now evangelical masses, something that is crucial to heal the profoundly politically divided Brazilian society.

A left-wing phenomenon in the religious field, Liberation Theology was constituted as a robust movement in Latin America after the modernising transformations brought by the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965). Led by Catholics, it also congregated people from other denominations, especially Reformed churches.

Liberation Theology has always emphasised the concrete social and economic changes that could improve the lives of millions of impoverished Latin Americans. Its approach to spirituality was profoundly determined by the sociological and political analysis of the oppressive conditions of existence in the region. Such a perspective was consecrated in the notorious formulation of the Catholic Church’s so-called ‘preferential option for the poor’.

Liberation Theology has always emphasised the concrete social and economic changes that could improve the lives of millions of impoverished Latin Americans. Its approach to spirituality was profoundly determined by the sociological and political analysis of the oppressive conditions of existence in the region. Such a perspective was consecrated in the notorious formulation of the Catholic Church’s so-called ‘preferential option for the poor’.

The theological reflections of Liberation Theology’s major thinkers, such as Brazilian Leonardo Boff and Peruvian Gustavo Gutierrez, resonated with thousands of basic ecclesial communities (known as CEBs in Portuguese), local groups that gathered to discuss the Bible and their social struggles with great autonomy from the Church’s structure.

Although the movement retained social relevance until the 1990s, it had to face aggressive internal criticism. In 1985, the Vatican imposed an “obsequious silence” on Boff for one year; for decades, many local cardinals and bishops used to censor progressive priests.

The movement also suffered with the offensive of the neo-Pentecostal churches that began to grow in poor, working-class neighbourhoods all over Brazil in the 1980s.

Since then, Liberation Theology declined as a social phenomenon and many traditionalists have pointed to it as being responsible for the massive reduction in the Brazilian Catholic Church’s flock.

“The process was disturbed by 34 years of conservative papacies, with Pope Saint John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI,” Carlos Alberto Libânio Christo, a major Liberation Theology author known in Brazil as Frei (Friar) Betto, tells Sight. “By censoring Liberation Theology and denying support to the CEBs, they made the poor migrate to the evangelical world.”

In the opinion of Frei Betto, the hierarchy’s suppression of the CEBs’ popular movement fostered clericalism – an excessive deference to the opinion of the clergy – in the Catholic Church, something Pope Francis has been adamantly combatting.

But the movement also had to deal with its own fragilities, according to some analysts.

Paulo Ueti, a Bible scholar and Anglican Alliance facilitator.

“Liberation Theology’s various expressions created little machines of social transformation, which is fair and undoubtedly worked well. But they left a blank space related to private spirituality and subjectivity.”

“Liberation Theology’s various expressions created little machines of social transformation, which is fair and undoubtedly worked well. But they left a blank space related to private spirituality and subjectivity,” reflects Paulo Ueti, a Bible scholar and Anglican Alliance facilitator. “This might have left an open door for other groups. Liberation Theology became institutionalised and began to operate as an analytical category.”

Lutheran pastor Romi Bencke, secretary-general of the National Council of Christian Churches of Brazil (known as ‘Conic’ in Portuguese), says one of the major flaws of Liberation Theology is that it never ceased to be patriarchal.

“The women’s theological production was always marginal in Liberation Theology. Even today, it’s mostly invisible for publishing houses,” she tells Sight.

For pastor Ariovaldo Ramos, who coordinates a network of progressive evangelicals in the country, Liberation Theology lacked “local sensibility for the poor people’s concrete anguishes”.

“Liberation theologists always explained the structural causes of the people’s suffering, but they forgot to address their immediate needs,” he says. “If my daughter is dying without seeing a doctor, of course it’s due to the absence of a decent public healthcare system. But I don’t care about it. I need someone to come to my house and tell her: ‘Talitha cumi!’ [Aramaic words contained in Mark 5 in which Jesus tells a dead little girl to “get up”].”

This kind of mystical intervention, profoundly based on the popular masses’ faith, has always been the most important element of neo-Pentecostalism in Brazil. In pastor Ramos’ opinion, that’s why it succeeded.

Romi Bencke, Lutheran pastor and secretary-general of the National Council of Christian Churches of Brazil.

“The CEBs [basic ecclesial communities] were social and spiritual protagonists. Many people who used to be part of them switched to neo-Pentecostalism.”

But most of the flourishing Brazilian neo-Pentecostalists gradually allied with far right-wing ideas, reacting with particular criticism to moral changes in society and in Christianism, explains pastor Ramos.

According to pastor Bencke, the growth of conservative religiousness in the 1990s can also be seen as a deliberate political effort to weaken Liberation Theology.

“The CEBs were social and spiritual protagonists. Many people who used to be part of them switched to neo-Pentecostalism,” she says.

Bencke believes that such an ultra-conservative theology has since infiltrated all Christian churches in Brazil since then.

“It’s not only an evangelical phenomenon. It’s also present in the historical Protestant churches and in Catholicism [with the so-called Catholic Charismatic Renewal]. This movement formed a Brazilian kind of Christian right-wing.”

Indeed, many of the religious leaders surrounding President Bolsonaro are not members of neo-Pentecostal churches, but are Presbyterians – like his ministers of justice and education – or Catholic – some of his closest political advisors are ultra-traditionalist Catholics under the influence of the US-based Brazilian author Olavo de Carvalho.

“So, we cannot pretend this phenomenon doesn’t relate to us [traditional Protestants and Catholics] and blame only the evangelicals,” pastor Bencke argues.

At a time when President Bolsonaro has lost support among many segments of the population due to his controversial management of the COVID-19 pandemic – he has continually attempted to minimise the seriousness of the disease and never imposed a federal quarantine in the country despite the fact Brazil now has seen more than 2.1 million confirmed cases and more than 80,000 deaths – it’s particularly intriguing to progressive theologists why so many evangelicals remain loyal to him.

Pastor Ronilso Pacheco.

“Evangelicals don’t see [President Jair Bolsonaro] as an exemplary brother in a moral perspective. They see him as a patron of their aspirations of conservatism.”

“Evangelicals don’t see him as an exemplary brother in a moral perspective,” says pastor Ronilso Pacheco, who recently published a book about black Liberation Theology in Brazil. “They see him as a patron of their aspirations of conservatism.”

If President Bolsonaro is personally an imperfect Christian – he has married three times, professes Catholicism and frequents evangelical services with his wife, he somehow personifies a set of ideas that have become dominant among neo-Pentecostals in Brazil over the past few decades which relate to a strong individualism in how they view their religion and society as a whole. Such ideology stands in opposition to the collectivist perspective of Liberation Theology.

Pacheco doesn’t see the evangelicals embracing progressive theologies in the short term, but he thinks that dialogue with those neo-Pentecostals at the bottom of the economic ladder will eventually be re-established.

“People in favelas have real needs. Their concrete realities open possibilities for us,” he says.

While upper-class evangelicals usually support Bolsonaro’s far-right platform due to a deliberate choice, Black, poor neo-Pentecostals typically have a less ideological closeness with the high-ranking pastors who endorse the President, pastor Pacheco argues.

“A local minister of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God [one of the most powerful evangelical churches in Brazil] many times manages the life of his community with a certain autonomy from the headquarters,” he adds.

The resurgence of a contemporary Liberation Theology, concerned with Blacks, Indigenous populations, women, and other minorities may enable a new dialogue with neo-Pentecostals, according to Paulo Ueti.

“Such theologies are closely linked to popular movements and have the potential of addressing not only theologists and pastors but also the ordinary people,” he argues.

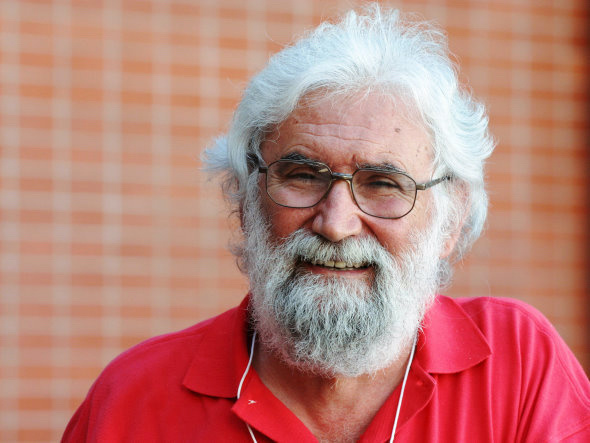

Leonardo Boff. PICTURE: Supplied.

“The Brazilian people [are] deeply religious, even mystical. [They don’t] follow orthodoxy and the Catechism. If someone talks about God, Christ, and the Bible, people just follow.”

The main challenge at this point, according to Leonardo Boff, is to encourage many evangelical segments to take up again the humanitarian values of Jesus, based on “love, solidarity, and mutual service”, in opposition to the official line of many “deceitful ministers”.

“The Brazilian people [are] deeply religious, even mystical,” he tells Sight. “[They don’t] follow orthodoxy and the Catechism. If someone talks about God, Christ, and the Bible, people just follow.”

Ecumenism, Boff argues, will be the natural result once a successful dialogue is established again with the evangelical masses.

“We Catholics shouldn’t be worried about the church that the people will frequent. The true church is the one which works for justice, attends the demands of the neediest ones, and persuades the state to organise economy for the common good.”