In the light of recent Black Lives Matter protests in Australia, CHRISTOPHER GILBERT speaks with Australian Aboriginal Christian leaders about the response to the movement in Australia and their hopes for change…

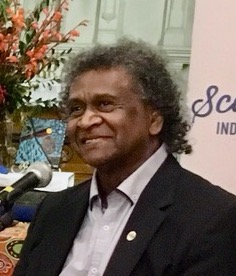

On the day of Sydney’s Black Lives Matter march on 6th June, Pastor Ray Minniecon was torn. He was hosting 300 attendees at an international online conference for the North American Institute of Indigenous Theological Studies – part of a post-graduate course it had taken him 20 years to bring to Australia – which meant he couldn’t attend.

But, as someone who has spent more than 30 years working for Aboriginal communities – including at one point as the national director of World Vision’s Indigenous programs and now as the minister leading Scarred Tree Indigenous Ministries based at St John’s Anglican Church in the Sydney suburb of Glebe, the march really mattered to him.

“We have so many deaths in custody it’s just, if you’re looking at Aboriginal pastors, most of us are burying our people,” he said afterwards. “We just get tired of burying our people and visiting them in jails. We do a lot of visitation and all that kind of stuff. So we’re working our butts off to try to prevent these things.”

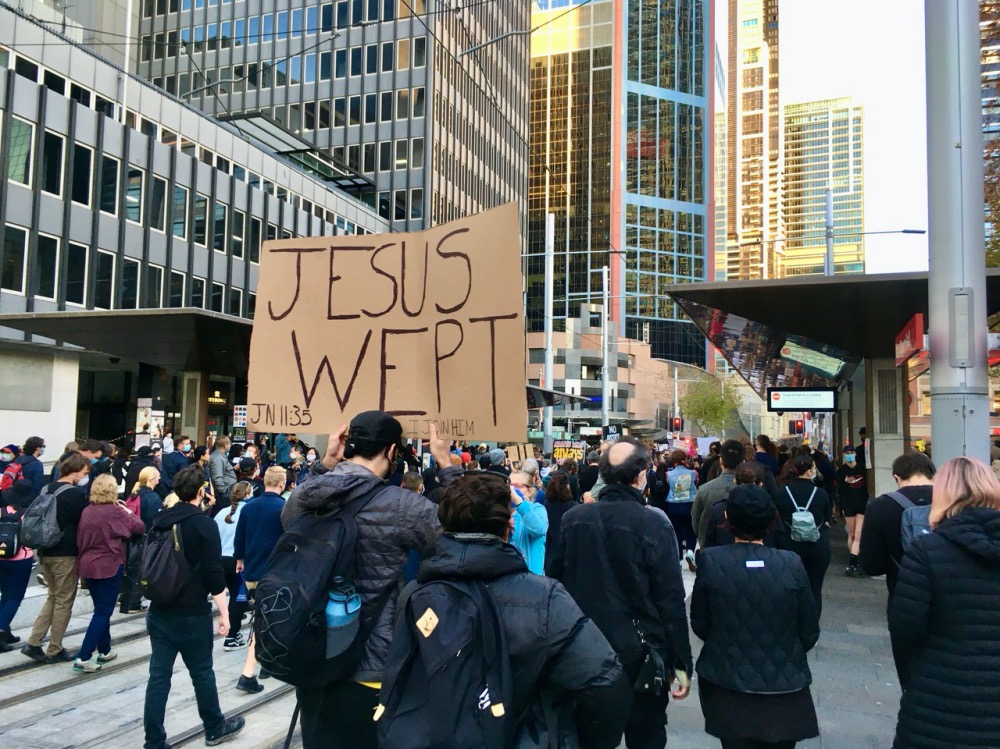

The Black Lives Matter protest in Sydney on 6th June, PICTURE: Christopher Gilbert.

Based on police estimates, more than 80,000 thousand Australians rallied in every capital city and many regional centres in support of Indigenous Australians on that June weekend, protesting an accelerating number of black deaths in custody. Rally organisers quoted a two year investigation of census data by The Guardian which found the figure stood at 432 deaths in police custody since 1991, a figure which has since increased to 437. And, as Alison Whittaker, a research fellow at the University of Technology Sydney, noted in an article on The Conversation recently, no Australian law enforcement official has been held responsible for any of these deaths.

For many Aboriginal Christian leaders like Minniecon, the matter was urgent enough to encourage all Australians and especially those involved in the Christian churches, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, to march in protest. They say they are glad about the turnout and the tone of the rallies, which police and media outlets described as peaceful and orderly. But many leaders said that they’ve learned to expect the absence of white churches in moments like this. On this occasion they weren’t wrong.

Ray Minniecon. PICTURE: Chris Gilbert

“This one is different. There’s a nice spirit about it and people here who have never come out to support us before, lots of white faces in the crowd. It gives me hope that this time something will change.”

– Margaret Campbell, a 70-year-old Dunghutti woman who attended the Sydney march.

Citing the COVID-19 pandemic as a reason to stay away, the Prime Minister of Australia, Scott Morrison, warned people against attending. In Sydney, the police asked the courts to block it, but a last minute Court of Appeal ruling allowed the rally to proceed. Organisers reinforced hygiene safety, repeatedly calling for distancing, and sent volunteers through the crowd with free facemasks and bottles of hand sanitiser. Most of the crowd in Sydney wore masks.

Among the 20,000 people who gathered in Sydney was a 70-year-old Dunghutti woman, Margaret Campbell, who stood on the Town Hall steps surveying the scene. She said she was optimistic despite being at many rallies for Aboriginal justice over the years that often went unnoticed.

“This one is different,” she said. “There’s a nice spirit about it and people here who have never come out to support us before, lots of white faces in the crowd. It gives me hope that this time something will change.”

Some 850 kilometres north, Aboriginal elder Aunty Jean Phillips was equally optimistic. She has served the spectrum of Australian churches as an independent minister for more than 60 years seeking justice for the poor and marginalised people of Australia, of which Aboriginal people make up a disproportionate part. At more than 80 years-of-age she joined an estimated 20,000 marchers in Brisbane.

“I’m really encouraged with the numbers of people there, particularly young people, probably some of them the first time they’ve ever heard or seen anything about Aboriginal people,” she told Sight.

Phillips said that in this moment, which many are calling a “tipping point”, she wants to see all churches becoming more open to the idea of engaging with Aboriginal Christian leaders in seminars on the justice issues which she said have been so long unaddressed.

“We are called to do justly,” she said. “And if we could get together now and talk more, people would really understand what we’re on about. It can’t end with the march.”

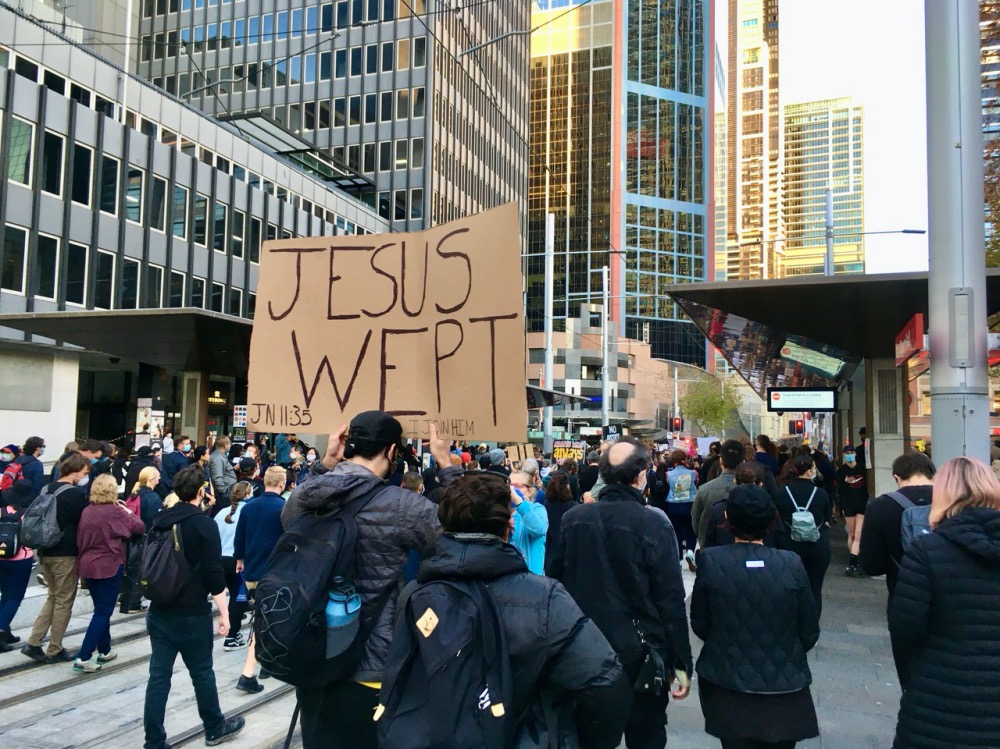

A banner at the Black Lives Matter protest in Sydney on 6th June. PICTURE: Christopher Gilbert

Some 2,000 kilometres to the south-west can be found the South Australia-based Raukkan Community. Ngarrindjeri man, Clyde Rigney, is the vice chair of the community board and a follower of Jesus. He is troubled that for more than 200 years, most Australians have no inkling of what Aboriginal people face. In his experience not many seem to want to know, though he hopes daily for the peace of Australia.

“I’m a child of the Fifties; my parents were born in the Thirties. We grew up on a mission, a mission which was run by churches and Christian folk,” he explained to Sight. “We’re talking about the ‘protection’ period that followed the colonisation period. I’m always talking about our shared history.”

Rigney’s experience is that most Australians don’t actually talk about this shared history of colonisation and “protection”.

“In some ways it’s easier to see Black Lives Matter and Aboriginal deaths in custody as an issue when we look at what’s happening in the US,” he says, noting that First Nations people in the US experienced the church-mandated dispossession through colonisation almost 200 years earlier than in Australia.

“[W]e have lots of people mak[ing] comments about Black Lives Matter like it’s a now thing. For First Nations people and people in colonised countries, this has been a forever thing. If you haven’t got that context, you don’t really know what this is about.”

– Ngarrindjeri man Clyde Rigney, vice chair of the South Australia-based Raukkan Community.

The latter comment refers to dispossession of native peoples that was originally permitted following the pronouncement of Pope Nicolas V in 1454 for the European age of exploration: the doctrine of terra nullius or “empty lands.” Eighteenth century British lawyer, William Blackstone, later refined it as justification for the colonising of Australia.

“But [in the protection period] from 1857 to 1967, that’s 110 years, we were on missions without a voice,” said Rigney. “When we take that into account, is it any wonder that people want their voice heard now? So we have lots of people mak[ing] comments about Black Lives Matter like it’s a now thing. For First Nations people and people in colonised countries, this has been a forever thing. If you haven’t got that context, you don’t really know what this is about.”

Such a sentiment is a common refrain among leading Indigenous Australians who follow Jesus. And, for one man, it’s a song.

Scott Darlow, a First Nations singer/songwriter from Melbourne is a proud Yorta Yorta man who says he loves Jesus and takes to heart His greatest commandment contained in Luke 10, to love God and our neighbour. His latest hit single, You Can’t See Black in the Dark, features lyrics dealing with the shared history of Australia that Rigney speaks about:

Been here longer than time

And Our blood’s soaked into the earth below

I can still see the line

Kept us separated from each other that’s the way it was

In 67 my name, was recognised

But do you recognise the pain

Are you released from your shame

While our kids are locked up like a dog inside a cage

I’m not blinded by the sins of the past

We’re burning. But we never struck the match

I’m gonna make a fire from this spark

We’re gonna light it up, you can’t see black in the dark.

Darlow read the reactions that came from some sections of the community about the marches and hopes for a change of perspective. He also noticed in Melbourne what was clear in Sydney and Brisbane marches: non-Aboriginal churches were conspicuous by absence.

“All these people that are jumping up and down about how could you be so selfish during a pandemic?“ he tells. “Instead of looking at that, look at the reality that there are people who are genuinely smart enough to realise that they’re risking their health. They are so desperate through generational damage and trauma and the history of this country that they’re going, ‘Maybe, just maybe we might be heard this time around’. We know that there’s a health risk but we’re also desperately passionate to see change for our children that we’re actually prepared to risk our health during a pandemic.”

While many Christians in Australia are supportive of the movement (as well as in the US, where conservative Christian Republicans are among those who regard Black Lives Matters favourably), some of the reactions to the marches from among the Christian community in Australia have been fierce, including from the Australian Christian Lobby – managing director Martyn Iles labelled the Black Lives Matter movement as Marxism in a recent video – and from a number of white pastors. In one case, an Indigenous pastor who wished to speak with Sight was admitted to hospital because of stress resulting from the strength of their criticisms of his role as a march organiser. He was too unwell to follow through with the interview.

Sandra and William Dumas, senior pastors of the Gangallah church community at South Tweed Heads on the New South Wales and Queensland border. PICTURE: Supplied.

For Sandra Dumas, senior pastor of the Gangallah church community at South Tweed Heads on the New South Wales and Queensland border, the Black Lives Matter marches were a deep cry from the heart of the nation.

“We think that the march itself was brilliant,” she says. “It’s the only way that you’re going to expose what’s going on in our nation. Our church will always turn out to march for NAIDOC week and Reconciliation Week.”

On the lack of church presence in Brisbane, she says most Indigenous movements like Reconciliation Week and NAIDOC [National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee] Week have all come from a place where “[Aboriginal] men of God like William Cooper and Garth Nichols stood up and said ‘This doesn’t add up, something’s not right here’. They believed what the word of God says, that there’s justice, there’s equality for all.”

Dumas says the justice movements started with prayer and collaboration, where people came together to talk about injustice or inequality.

“It has been a God act on these occasions.” she explains. “And Black Lives Matter is no different. It’s a cry that’s been heard from our nation and our churches are still not listening.”

Correction: The location of the Gangallah church community has been corrected from Fingal to South Tweed Heads.