KAREN SWALLOW PRIOR, in an article published by Religion News Service, argues that the power books have is not in what they tell, but how they tell…

Via RNS

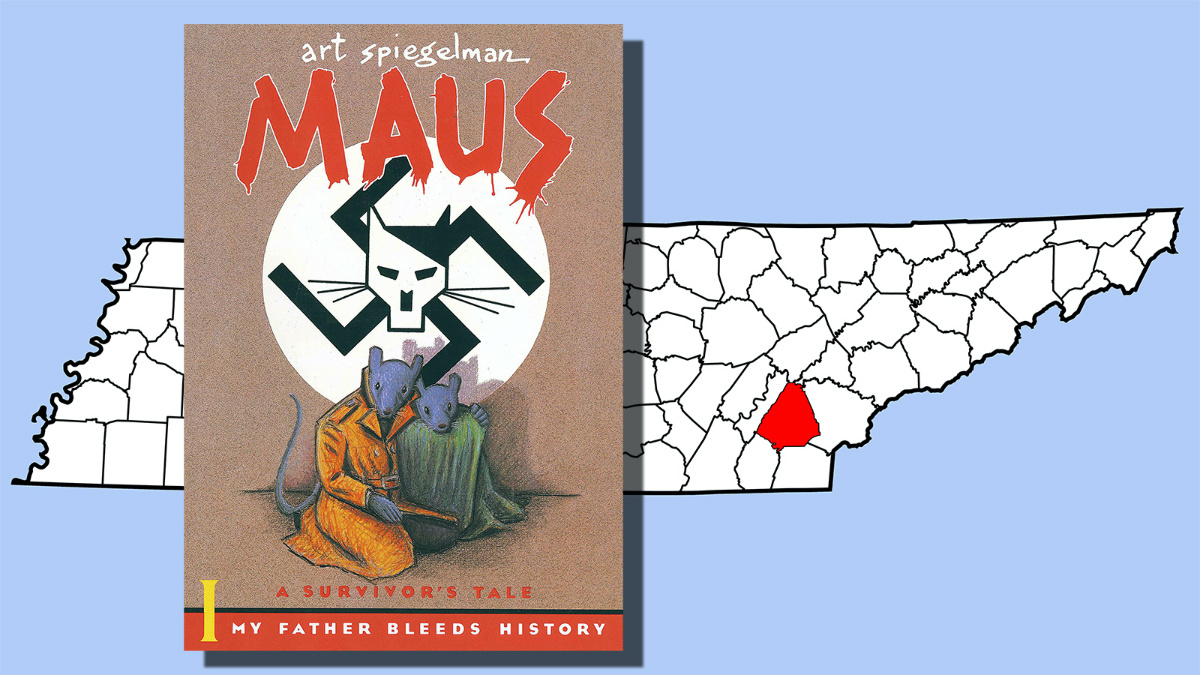

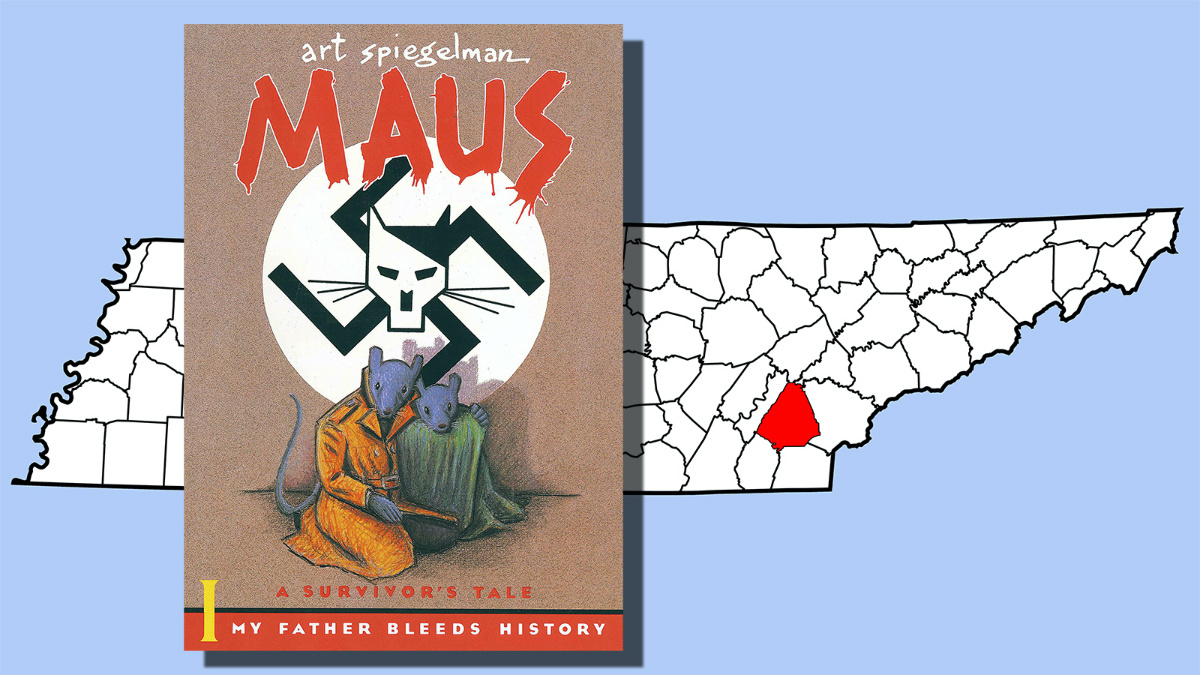

Last month, a school district in Tennessee voted to remove from its reading lists the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman, which imaginatively retells the story of the author’s Jewish parents, particularly the father’s experiences as a Holocaust survivor, through a fictionalised tale of a family of mice persecuted by cats.

Such material – a reflection of actual events that happened to actual people – is indeed heavy reading for adults, let alone for young people. It’s a story we would wish never needed to be told. But these stories did happen and do happen.

The cover of “Maus” by Art Spiegelman, left, and McMinn County, red, in eastern Tennessee. PICTURE: RNS illustration

The decision of when it is appropriate for children to face such truths about our world is not an easy one, and differs from child to child. One of the great gifts of good literature is that it allows us to learn about the world, both its goodness and its lack of goodness, in ways we could never experience for ourselves.

However, the horror of this real-life story isn’t the reason Maus was removed from McMinn County’s school curriculum. Rather, the school board removed it because of an illustration of a nude character and the book’s “inappropriate language.”

“What’s more important than what we read is that we read.”

It might be one of the more puzzling challenges to books in schools, of which it is only the latest: The American Library Association reported that “273 books were affected by censorship attempts” in 2020 alone.

It’s important to note that books are selected and unselected for library shelves and schools curriculums all the time, and not selecting one book or another is not necessarily censorship. Nor is updating a curriculum by replacing lesser books with better ones censorship.

Even so, it’s not surprising that the removal of Maus in a small county south-west of Knoxville made such big news. Politicians, pundits and grifters on both sides of the political aisle have a lot to gain by whipping people into a frenzy and profiting from the polarisation. The fact that the decision took place at a time when anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial are on the rise worldwide adds to its significance.

But rather than discuss the merits of Maus (it is a very important and powerful work of literature), its age-appropriateness (most 10-year-olds likely see worse things on their phones every day) or the specific ways in which this decision was handled, the event offers us an opportunity to consider the power books have not in what they tell, but how they tell.

What’s more important than what we read is that we read.

This has always been true. But in this digital age in which we are assaulted all day long, to deleterious effect, by images, music, pop-up ads, headlines, clickbait, TikTok videos, Facebook videos, Instagram videos, cat videos, dog videos and pimple popping videos (the list is exhausting!), taking time to read is more important than ever – especially for those minds that are still growing and developing.

Sadly, a new report from National Assessment of Educational Progress shows that the number of American nine and 13-year-olds who say they read for fun on an almost daily basis has dropped from nearly a decade ago to the lowest levels since at least the mid-1980s.

In my book On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books, I argue that reading literature doesn’t just inform us in the way a newspaper article does, for example. Rather, reading literature forms us.

How does reading form us? Philosophers, critics, cognitive scientists and book lovers have been answering that question, in many different ways, for thousands of years. I think within our current context – one in which reading good words and reading them well is rarer and rarer, whether because of our own choices or circumstances beyond our control – there are some new, or newly important, answers.

Reading literary texts requires and cultivates attentiveness. It requires and cultivates patience. It produces questions, challenges, understanding, delight, growth.

This is because words require interpretation, artfully used ones especially so.

We are living in a time marked by perhaps nothing more than impoverished abilities of interpretation. The polarization we are experiencing now is partly due to genuine disagreements, of course. But it is more often owing to our inability to correctly interpret one another, our words and ideas.

In fact, one of the most frequently challenged schoolbooks, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, offers an ironic lesson about this need for skills in reading and interpretation. The reason often given for removing this book is its alleged racism. But the book actually criticises, devastatingly, the racism of slavery. Recognising this fact requires not merely reading what the book says, but how it says it.

Literature – in ways that pictures and videos don’t – requires us to interpret because letters are symbols. They must be interpreted, or they are but squiggly lines on the page. The critical thinking inherent in the simple act of interpreting letters into words that form ideas is part of the very basis of modern civilization. (Interestingly, graphic novels like Maus complicate these requirements even further by combining texts and pictures in ways that ask for more interpretation by the reader.)

To put it most generally and succinctly, the form of literature inherently promotes critical thinking by requiring an interpretation. Books ask readers to consider things rather than do them. Learning to read well requires reading that challenges us, requires us to pay attention, ask questions, wonder and think.

While parents should certainly be involved in deciding what their children read, and while schools should guide these choices carefully, what ought to unite us is the desire to encourage one another to read more, not less.

Instead of taking Maus off the shelf, families might read it, and so many other books, together – then weep, wonder and pray together, too.

Karen Swallow Prior is research professor of English and Christianity and culture at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and the author of several books, including On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books (Brazos 2018). Her writing has appeared at Christianity Today, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, First Things and Vox, among others.

This article contains affiliate links.