FILIP KOSTELKA and ANDRÉ BLAIS investigate, in an article published on The Conversation, the reasons for declining election turnouts around the world…

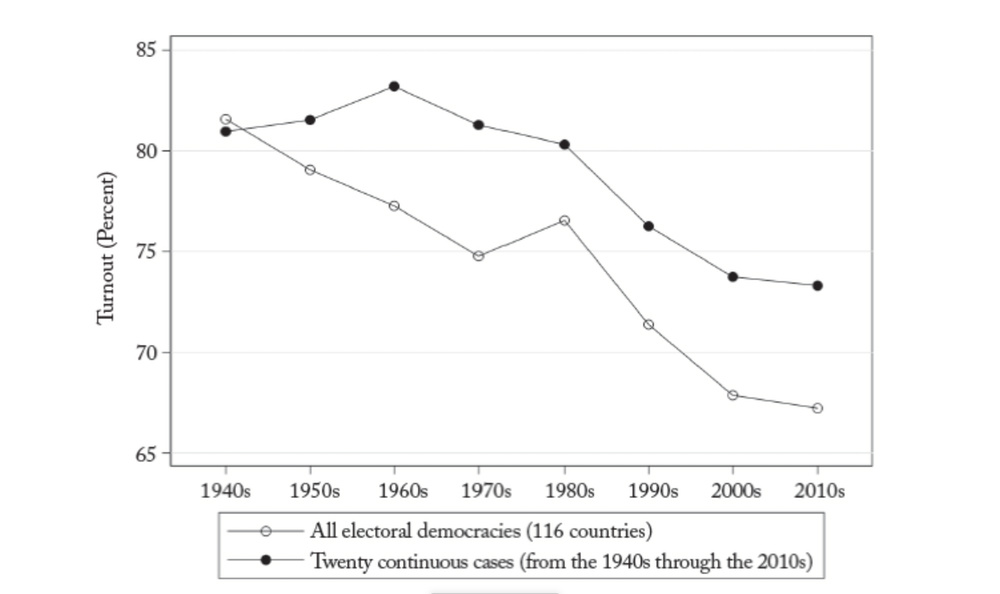

Any democratic nation in the world holding a legislative or presidential election in the late 1960s could expect around 77 per cent of its citizens to turn up to vote. These days, they can expect more like 67 per cent – a decline that is both problematic and puzzling.

Research shows that low turnout is bad for democracy. It usually means that socio-economically underprivileged citizens vote less and, as a result, public policies benefit the rich. Politicians feel less under public scrutiny and turn a deaf ear to the needs of the wider public. Instead of formulating general public policies serving society at large, governments can more easily target benefits to their core supporters.

A sign is pictured during Canada’s federal election, in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, on 20th September. PICTURE: Reuters/Lars Hagberg.

And the decline has occurred against a backdrop that might be more likely to imply an increase in election participation. Educational attainment has increased since the 1960s, for example, and election results have become closer – which would be thought to mobilise electorates.

Scholars and pundits have offered several hypotheses for the decline. Some think that political dissatisfaction has increased and keeps people away. Others cite economic globalisation, suggesting that if national governments hold less power, the stakes of their national elections are lower and people won’t see the point in taking part. We tested all of these hypotheses in the most extensive cross-national study of voter turnout to date, drawing on 1,421 national elections, and 314,071 individual observations from high-quality post-electoral surveys.

Evolution of voter turnout in national elections 1945-2017

Generational shift

Our statistical analysis did not find support for many of the popular explanations. Instead, we identified two main causes. The first is a generational change resulting from economic development. People born into more affluent societies develop values that are less conducive to participation. Once countries reach a certain level of economic wealth, new generations become less deferential to authorities and less likely to conceptualise voting as a civic duty. They go to the polls less often than their older counterparts, who were socialised in earlier stages of economic development. The mechanical process of generational replacement, whereby new generations’ share in the electorate grows as older generations pass away, accounts for 56 per cent of the voter decline.

The other main cause, responsible for 21 per cent of the decline, is the rise in the number of elective institutions. When elections are more frequent, voter fatigue sets in and people’s interest in taking part slides. In Europe, the number of elective institutions increased by 34 per cent since the 1960s. This was driven by European integration, state decentralisation, the frequent use of direct democracy, and institutional reforms such as the introduction of directly elected presidents. If voters are asked to vote nearly twice a year, like in France, some of them will get fed up and not bother.

Further to fall?

The generational nature of the problem suggests that turnout may continue to drop. But this isn’t inevitable. While new generations vote on average less than older generations, they do mobilise in particularly polarised contexts where a lot seems at stake. For example, the most recent presidential election in the United States in November 2020, in which the controversial incumbent Donald Trump sought re-election, yielded the highest voter turnout in the US for 120 years.

The rising salience of cultural and environmental issues, which new generations care deeply about, could likewise offset some of the generational declines in turnout.

Public authorities can also help by reducing the number of times citizens are called to the voting booth. This can be achieved without reducing citizens’ rights by reorganising election calendars and combining different election types on the same day.![]()

Filip Kostelka is a lecturer (assistant professor) in government at the University of Essex and André Blais is a full professor in the Department of Political Science at the Université de Montréal. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.