In an article first published on Religion News Service, JAMES ACKERMAN, president of Prison Fellowship in the US, writes about why words matter when describing people in reference to the prison system…

Via RNS

I joined the staff of Prison Fellowship in 2016 with a decade of experience as a prison ministry volunteer. Our founder, Chuck Colson, was a mentor of mine, and I shared his vision for restoring those in prison. But I paid little attention to the names I used for people I was here to serve. I used common terms like felon, offender, convict and shrugged it off – until I understood that labels have the power to shape how people with a criminal record view themselves and how society thinks of them.

Language shifts aren’t new, but they are important to underscore personhood and get away from an “us versus them” mentality. On the other side of every label we give, there is a human being made in the image of God. Men and women who have been involved in the justice system are not the sum of their conviction history.

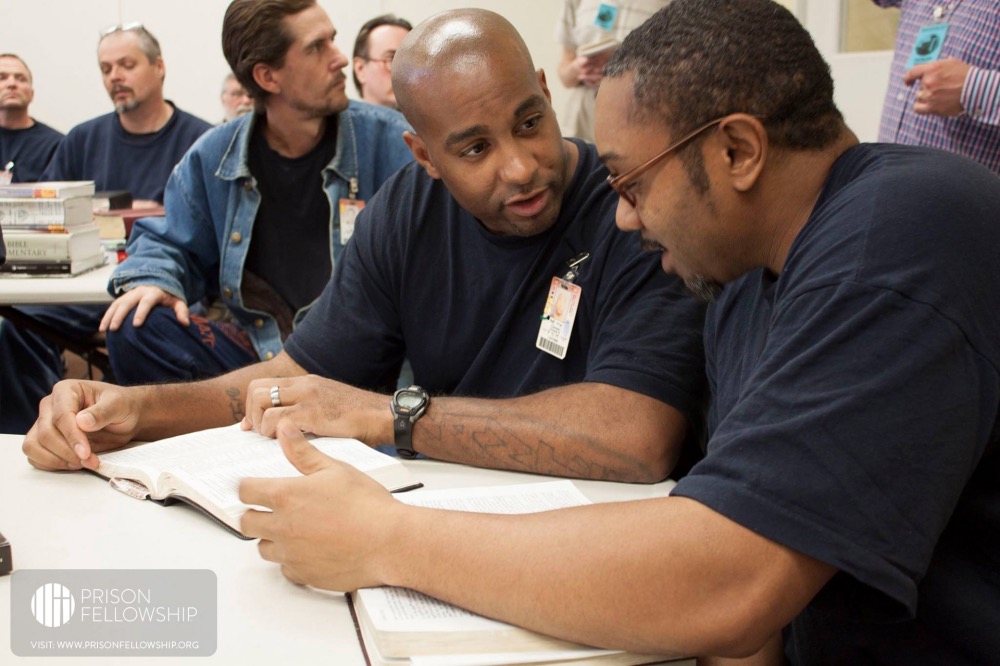

Two men read and discuss the Bible together. PICTURE: Courtesy of Prison Fellowship

Prison Fellowship might be the first group to survey Americans regarding their use of the term “returning citizen” for people coming out of prison. According to the Barna poll results, around one in four Americans claims to be familiar with the term, which is widely used in the justice reform community.

Among those who identify as practicing Christians, a majority are open to using more positive, person-first language, with only 23 per cent preferring traditional labels like felon or offender. Among these, men are much more likely than women to prefer traditional labels (30 per cent versus 17 per cent), as are evangelicals (33 per cent) and those with higher incomes (36 per cent).

“Prison Fellowship might be the first group to survey Americans regarding their use of the term ‘returning citizen’ for people coming out of prison. According to the Barna poll results, around one in four Americans claims to be familiar with the term, which is widely used in the justice reform community.”

Coming from the world of Hollywood and media, I thought headlines like “Drug-Dealing Ex-Convict Becomes a Pastor” packed a punch. The language was dramatic and jarring, especially in light of the new identities that so many of our program graduates embody (eg hardworking employees, doting parents, good citizens). But some mindful colleagues of mine challenged me to realise the impact of using such words.

Convict and offender clearly tie someone to the worst thing they’ve ever done. The word inmate is generally paired with a prison ID on a uniform (“inmate 12345”), inevitably reducing the one wearing it to a number. Even to call someone an addict is to verbally equate the person with the habit. (Some victims of crime even prefer to be called survivors, because they want to see themselves as who they really are and not what happened to them.)

Language changes culture, and culture changes law, not the other way around. And if we as Christians don’t change the culture, who will? There are one in three adults with a criminal record in the United States today facing untold obstacles to a second chance after paying their debt to society.

We believe people have inherent, God-given worth; our language must affirm their personhood. They are people with a criminal record, incarcerated men and women, people who struggle with addiction or troubled pasts. This is not a cry for political correctness. It is a call to create a culture that upholds people’s potential, rather than one that holds them back with harmful stereotypes. Words should affirm their whole identity, including their capacity to change and grow.

Since 2017, Prison Fellowship has recognised April as Second Chance® Month, a nationwide celebration of second chances and an effort to unlock bright futures for people who have paid their debt to society. At one event last year, we met a man named Lance who had served time in prison after causing a car accident that took his best friend’s life. He was open about his story, from recovering from alcohol addiction and serving a sentence to struggling to forgive himself and find housing and employment.

As Lance shared: “I will sit down [in a job interview] and say, ‘Look, I’m going to tell you exactly who I am to start this conversation, so you know who you’re dealing with. I have a felony.’ [These] people see me around town, and they’ll say to me, ‘I had no idea.’ That’s kind of the point. The point is that I’m a person, and you know me as a person.”

I remember the heroes of the Bible we look up to, not in spite of their worst choices, but because of God’s power to redeem their lives. Serving him, the ultimate author of second chances, the church has a role to play in pursuing a more restorative justice system. Names clarify the world around us and carry the weight to redeem or condemn. It’s a heavy truth I’ve learned to embrace. It can be as simple as using different language tonight at your dinner table.

James Ackerman is president and CEO of Prison Fellowship, the largest Christian non-profit in the US serving prisoners, former prisoners and their families.