In an article first published on The Convversation, RICK SARRE of the University of South Australia, says it’s time we paid tribute to the thousands of Australia’s “largely forgotten” conscientious objectors…

As we commemorate the centenary of the Armistice, it is appropriate that we pay tribute to the thousands of largely forgotten people who formed a significant social and political coalition at the time of the first world war: those who fought against conscription, and against the war, including a significant number of conscientious objectors.

Military registration and training for all Australian men aged 18 to 60 was compulsory from 1911. But there was no provision in Australian law that required men to enlist for active service overseas. Signing up for such service was voluntary, and with the promise of a short war, there was no difficulty for recruitment officers finding their men.

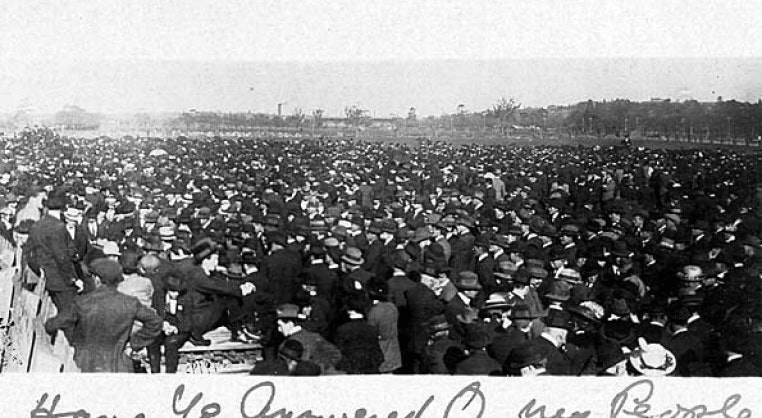

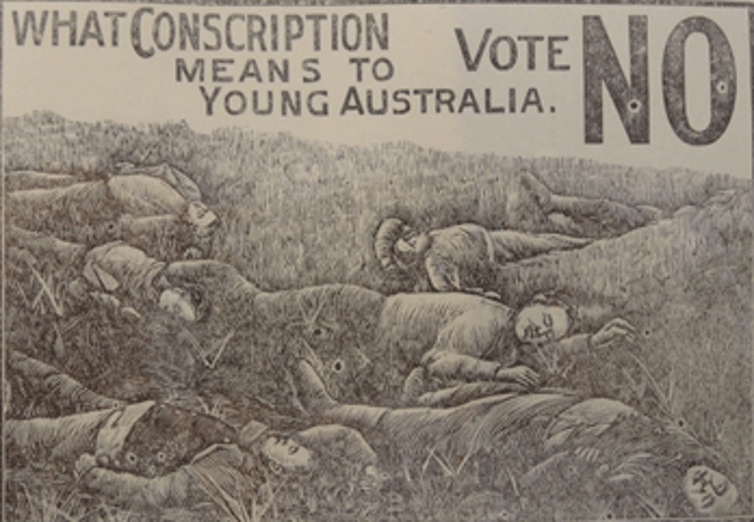

An anti-conscription rally in Melbourne, 1916. PICTURE: Heritage Council of Victoria

However, as news of the horrendous losses at Gallipoli from April to December 1915 and the slaughter on the Western Front from mid-1916 filtered back to Australia, enthusiasm for overseas duties began to wane.

“It is regrettable that Australia has no public memorial to our forebears who campaigned against compulsory military service, and the war itself, for reasons of conscience and faith. As we commemorate the centenary of the Armistice, there is no better time to remedy that oversight. “

“

Australia was not meeting its recruitment target. Only about a third of eligible men were volunteering.

Labor Prime Minister Billy Hughes determined that the only way to increase enlistment numbers was to impose conscription. He decided to hold a plebiscite (sometimes referred to as the “conscription referendum”) to carry out what he saw as his obligation to the Empire, and to do so with the consent of the Australian people.

But there were many vociferous voices from the trade union movement, the Labor Party and an active women’s coalition campaigning for a “no” vote. Religious adherents, too, found themselves well represented in the “no” campaign, with many Catholics, Quakers, Christadelphians, Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses in the forefront of the pacifist movement.

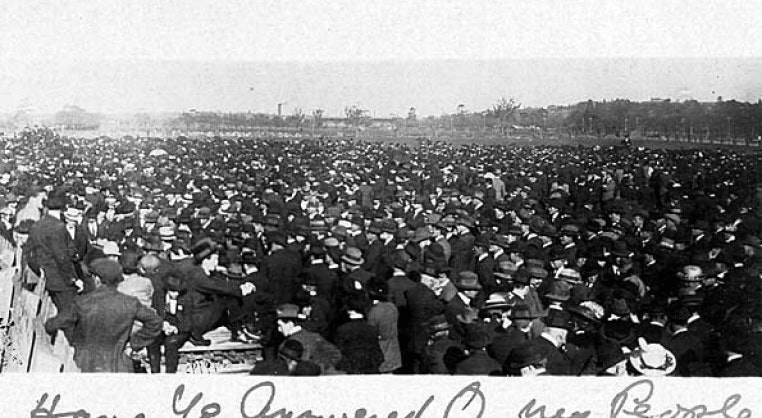

Archbishop Daniel Mannix was a leader in the Catholic Church in Melbourne. He took a strong stand against conscription, adding that the war was “just an ordinary trade war” driven by trade jealousy. Conscription, he maintained, would simply reinforce “class versus class” social injustices.

Remember, too, that the British had, in April, 1916, put down with force the Easter Rising in Ireland. Almost 2,000 Irish were sent to internment camps. Most of the leaders of the Rising were executed in May, 1916. Mannix was Irish-born.

Archbishop Daniel Mannix. PICTURE: National Museum of Australia.

Margaret Thorp, a Quaker, was another strong voice in opposition to the war, and critical of the support for the war by the mainstream churches. A member of the Anti-Military Service League, she later joined others to inaugurate a branch of the Women’s Peace Army in Australia and, later, a branch of the Sisterhood of International Peace that supported the international No-Conscription Fellowship.

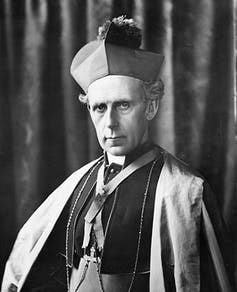

On 28th October, 1916, Prime Minister Hughes put the conscription ballot to the vote. It was defeated by a margin of three per cent.

The following year, Britain sought a sixth Australian division for active service. Australia had to provide 7,000 men per month to meet this request. But voluntary recruitment continued to lag behind requirements. On 20th December, 1917, Hughes put a second conscription ballot to the people. It, too, was defeated, this time by a larger margin (seven per cent). The war continued to the Armistice with volunteers only.

By the end of the war, over 215,000 Australians had been killed, wounded or gassed. Only one out of every three Australian men who were sent abroad arrived home physically unscathed.

During the 20th century, Australian law developed a variety of positions on conscientious objection. Such status today relies on an applicant meeting the requirements of the Defence Act 1903 as amended in 1939. Conscientious objectors need not have deeply held religious beliefs. But they must be able to ground their objection in moral beliefs, and be able to articulate them.

An anti-conscription poster. PICTURE: Parliament of Australia.

People who were not able to be officially recognised as conscientious objectors in Australia during the first world war were prosecuted when they failed to register. While historical records are impossible to collate accurately on this subject, some 27,749 prosecutions had been launched across the country by 30th June, 1915. Stories of the tragic social consequences for these men, and for conscientious objectors, are legion. Objectors particularly were often maligned as cowards and self-seekers. But the historical records illustrate that theirs was not an easy path. They did not lack courage. In many respects, the choices made by conscientious objectors required a greater determination and certainty of belief than was needed by the men who enlisted voluntarily.

There is a permanent memorial for conscientious objectors in Tavistock Square, London, and one is planned for Edinburgh, Scotland. There is a tribute at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City for the pacifists Joseph and Michael Hofer, who died in Leavenworth Prison in 1918 while incarcerated for refusing military service.

It is regrettable that Australia has no public memorial to our forebears who campaigned against compulsory military service, and the war itself, for reasons of conscience and faith. As we commemorate the centenary of the Armistice, there is no better time to remedy that oversight.![]()

Rick Sarre is adjunct professor of law and criminal justice at the University of South Australia. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.